Asian Review for Public Administration (ARPA)

Open Access | Research Article | First published online December 20, 2023

Vol. 31, Nos. 1&2 (January 2020 to December 2023)

Surviving the Crisis: Making Intergovernmental Relations Strong for Fighting the Pandemic, Case from Nepal

Trilochan Pokharel

Trilochan Pokharel

"Cite article"Pokharel, T. (2020-2023). Surviving the Crisis: Making Intergovernmental Relations Strong for Fighting the Pandemic, Case from Nepal. Asian Review for Public Administration, Vol. 31, Nos. 1&2, 23-46. |

| ||

Abstract: The aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic is still scary for many countries. Despite having a relatively lower number of casualties compared to some advanced countries, the developing and transitional countries witnessed social and economic impacts. Nepal, an emerging economy, has been accelerating to institutionalize the recent constitutional and political transformation implemented through the 2015 Constitution. The recently adopted federal form of governance has shared state authorities among the federal, provincial, and local governments including management of health services and other emergencies. This new set of governance arrangements has been expected to deliver public services and protect people’s fundamental rights in an efficient, coordinated, and economic way. For a disaster-prone country like Nepal, the COVID-19 crisis exposed its weary and transitional crisis governance. Several gaps have been identified in the ways the government took initiatives. The major challenges were about the defined leadership roles, intergovernmental coordination, indicator-based financial allocation, and capacity of crisis management institutions, including the health care facilities. This paper analyzes Nepal's efforts to manage COVID-19 in the broader landscape of political governanceand disaster risk profiles and offers insights on intergovernmental relations drawing from three rounds of surveys conducted between 2020 and 2021 among Nepal’s local governments.

The studies record a positive response to the functions of local governments as they felt accountable for addressing public concerns. It further reports a number of critical gaps in intergovernmental relations for dealing with COVID-19. Discrete leadership and poor vertical and horizontal coordination and communication, mismatch in funding and COVID-19 caseload and lack of post-recovery plan at all levels of the government made the crisis governance inefficient, increasing the burden on people. Extensive interactions and engagement, organized and collaborative leadership among the orders of the government and strengthening the capacity of the sub-national governments would be instrumental in dealing with such crises in the future.

The studies record a positive response to the functions of local governments as they felt accountable for addressing public concerns. It further reports a number of critical gaps in intergovernmental relations for dealing with COVID-19. Discrete leadership and poor vertical and horizontal coordination and communication, mismatch in funding and COVID-19 caseload and lack of post-recovery plan at all levels of the government made the crisis governance inefficient, increasing the burden on people. Extensive interactions and engagement, organized and collaborative leadership among the orders of the government and strengthening the capacity of the sub-national governments would be instrumental in dealing with such crises in the future.

1. Introduction and Country Background

Nepal is at the 107th position of 195 countries in the Global Health Security Index 2021, a global comparative index that measures the status of health governance in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic (Bell & Nuzzo, 2021). The index provides estimates on six categories of COVID management - prevention, detection and reporting, rapid response, health system, commitments to improving national capacity, financing, and global norms, and risk environment. Among others, the report further highlights two critical issues for dealing with a health crisis: a) insufficient health capacity and b) ineffective coordination among national entities and global organizations. Nepal’s rank is below the global average, indicating potential gaps in the institutional capacity of managing health crises. Considering the constrained healthcare capacity, this paper aims to explore the functioning of the newly implemented federal governance structure of Nepal following the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in 2015, particularly from the perspective of coordination among the orders of the governments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced all countries, especially the low- and middle-income countries that have a poor health governance system, to assess their health governance capacities and take necessary steps to be prepared for a better future. For a developing country like Nepal, surviving the crisis is always a social, political, economic, governance, and policy issue. This paper focuses on the aspects of intergovernmental relations for managing the health crisis.

Nepal is practicing three-tier multi-level governance with each level having constitutionally enumerated competencies including the management of health services. As the new governance architecture replaced the unitary form of governance with a devolved federal structure, the transition was accelerating, and Nepal was struggling to institutionalize the constitutional provisions by installing governance structures and procedures (Thapa, Bam, Tiwari, Sinha, & Dahal, 2019). Meanwhile, COVID-19 emerged as a real assessment of the country's capacity to deal with the crisis. Considering that public health is a shared responsibility among the levels of government, the theory of intergovernmental relations underscores effective interactions among the governing units are vital in delivering services efficiently. Such interactions should be defined by processes and institutions (Phillimore, 2013) that would facilitate different levels and actors of governance to function in a coordinated and cooperative manner.

Containing health crises is a testimony of functional relationships among orders of the governments as public health transcends the arbitrary political boundaries created for administrative purposes. Such expansions would require the public authorities to find ways to define and exercise both formal and informal mechanisms to remove barriers, intensify information flow, appreciate collaborative leadership, and promote interagency relations. In a multi-level government, the lower-order governments, particularly the local governments, serve as the first responder to public demands (Morphet, 2008; Acharya, 2018) through frontline delivery (Pokharel & Sapkota, 2021). The roles of local governments in dealing with COVID have been largely appreciated in many countries, as they have taken decisive roles to apply national policy standards in the local contexts (Democracy Resource Center Nepal, 2020; Silva, 2022). However, a relevant aspect to understand in the practice of multi-level governance is ‘how did the intergovernmental relations function in managing the health crisis?’, which is the central theme of this paper. The case from Nepal would advantage global readers owing to the nature of political, economic, and social transition propelled by new experimentation of governance structure.

For setting the context of Nepal’s overall healthcare governance, this paper provides the country context, disaster risk profile, health management system, survey introduction, and key findings of the study in a coherent framework.

Political economy background

Nepal has survived natural, social, economic, and political crises in the past. Situated between the world’s two big economies and populations, China and India, it is accelerating the institutionalization of stable governance and economic development. The political crisis of the recent past, a decade-long armed conflict between 1996-2006, and political maneuvering led to the introduction of a new Constitution in 2015. This Constitution transformed Nepal from a unitary centralized form of governance to a decentralized federal system. It also ended the conventional monarchical system with the adoption of the republic system. This new polity has allocated government business among three tiers- federal, provincial, and local- of government with defined responsibilities (exclusive and concurrent). The new governance arrangements have allowed Nepal to function in a more concerted and complementary way to deal with public problems, with sub-national governments having autonomy in several functions to deal with the issues in their jurisdictions. The governance of Nepal is now managed by 761 governing units (federation, 7 provinces, and 753 local units), each order having defined roles, but overlapping in some cases. Health is an example of such overlap.

With the new governance architecture in place, the three orders of the governments are taking initiatives to implement constitutional mandates. The Constitution safeguards the autonomy of federal units while qualifying the model of intergovernmental relationships based on the principles of ‘cooperation, co-existence, and coordination’. It implies that the federal units have to adhere to the basic principles of cooperative federalism while implementing the constitutional mandates (Dhungana, Pokharel, & Poudel, 2021). Such cooperation may be both formal or informal and vertical or horizontal. For the effective functioning of the federal units, the Constitution and subsequent legal arrangements propose several structural and institutional arrangements for promoting intergovernmental relations including fiscal relations (Pokharel & Sapkota, 2021).

Intergovernmental relations

The theories and literature do not have a universal definition of intergovernmental relations. However, they acknowledge the diversity in basic structures, mechanisms, and institutionalization (Poirier & Saunders, 2010), a common purpose is clear- mechanisms, institutions, and opportunities for interactions among the orders of government. It has mainly two dimensions- structural and functional. While the structural dimension is about the institutional arrangements defined by the policies and laws that provide official space for interactions among the levels of government, the functional perspective assumes to be organic and evolving. The governing units may explore and agree on the areas of cooperation, exchange support and provide the best compliments to deal with the issues of 'interdependencies and spill-over effects due to overlaps in functions and jurisdictions' (McEwen, Petersohn, & Swan, 2015).

The national government may be interested to use coordination mechanisms to make sure that its policies and standards are implemented by the sub-national governments, while the sub-national governments may take it as a space to negotiate power and finance. In an institutionalized system, the defined frameworks and practices provide inputs for intergovernmental relations and are more official in processes and contents. However, there are limits to formal relations. The constitution, legislation, and policies are closed documents while the relationship is fluid and dynamic. To deal with inter-jurisdictional dynamism, informal means of interaction, communication, and engagement are equally important, given that such practices would promote the public interests and are then backed up by a formal process. In the absence of an institutionalized system, the relations are person-centric, ad-hoc, intuitive, and non-transparent. It also lacks accountability among the actors.

As Nepal is at the early stage of institutionalizing the three-tier federal system, assessing the dynamics of intergovernmental relations merits attention for two reasons. First, as Nepal’s federal form of governance is unfolding, it adds value to understanding to what extent the formal structural arrangements of intergovernmental interactions are functional. Second, public health is a shared responsibility among the levels of government, demanding a concerted collaboration among the government spheres. It is worthwhile to weigh and expose gaps in the practice of cooperation and coordination while dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper, therefore, contributes to updating the literature on intergovernmental relations through fresh insights of practices drawing lessons from a country that is undergoing political and governance transition.

Disaster and health pandemic profile

Nepal is also considered a country in the high-risk zone for disasters such as earthquakes, floods, landslides, climate-induced disasters, and health pandemics. The recent earthquake of 2015 claimed the lives of nearly 10,000 people and caused an economic loss of over $7 billion, almost one-third of GDP (National Planning Commission [NPC], 2015). Table 1 shows the major disaster risks in Nepal. In addition, Nepal suffers several disease outbreaks of different scales owing to poor socio-economic status, insufficient health infrastructures, and inefficiency of health governance. For example, in 2009 an outbreak of cholera was identified in over 30,000 people with a casualty of over 500 in a western uphill district of Jajarkot (Bhandari, Dixit, Ghimire, & Maskey, 2010). The district falls into a category of low human development index of the total of 77 districts in the country. A recent outbreak in the mid-western southern plain district of Kapilvastu[1] is another piece of evidence to reiterate that Nepal is in the risk zone of a health epidemic.

Table 1. Disaster Risk Profile of Nepal

Nepal is at the 107th position of 195 countries in the Global Health Security Index 2021, a global comparative index that measures the status of health governance in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic (Bell & Nuzzo, 2021). The index provides estimates on six categories of COVID management - prevention, detection and reporting, rapid response, health system, commitments to improving national capacity, financing, and global norms, and risk environment. Among others, the report further highlights two critical issues for dealing with a health crisis: a) insufficient health capacity and b) ineffective coordination among national entities and global organizations. Nepal’s rank is below the global average, indicating potential gaps in the institutional capacity of managing health crises. Considering the constrained healthcare capacity, this paper aims to explore the functioning of the newly implemented federal governance structure of Nepal following the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in 2015, particularly from the perspective of coordination among the orders of the governments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced all countries, especially the low- and middle-income countries that have a poor health governance system, to assess their health governance capacities and take necessary steps to be prepared for a better future. For a developing country like Nepal, surviving the crisis is always a social, political, economic, governance, and policy issue. This paper focuses on the aspects of intergovernmental relations for managing the health crisis.

Nepal is practicing three-tier multi-level governance with each level having constitutionally enumerated competencies including the management of health services. As the new governance architecture replaced the unitary form of governance with a devolved federal structure, the transition was accelerating, and Nepal was struggling to institutionalize the constitutional provisions by installing governance structures and procedures (Thapa, Bam, Tiwari, Sinha, & Dahal, 2019). Meanwhile, COVID-19 emerged as a real assessment of the country's capacity to deal with the crisis. Considering that public health is a shared responsibility among the levels of government, the theory of intergovernmental relations underscores effective interactions among the governing units are vital in delivering services efficiently. Such interactions should be defined by processes and institutions (Phillimore, 2013) that would facilitate different levels and actors of governance to function in a coordinated and cooperative manner.

Containing health crises is a testimony of functional relationships among orders of the governments as public health transcends the arbitrary political boundaries created for administrative purposes. Such expansions would require the public authorities to find ways to define and exercise both formal and informal mechanisms to remove barriers, intensify information flow, appreciate collaborative leadership, and promote interagency relations. In a multi-level government, the lower-order governments, particularly the local governments, serve as the first responder to public demands (Morphet, 2008; Acharya, 2018) through frontline delivery (Pokharel & Sapkota, 2021). The roles of local governments in dealing with COVID have been largely appreciated in many countries, as they have taken decisive roles to apply national policy standards in the local contexts (Democracy Resource Center Nepal, 2020; Silva, 2022). However, a relevant aspect to understand in the practice of multi-level governance is ‘how did the intergovernmental relations function in managing the health crisis?’, which is the central theme of this paper. The case from Nepal would advantage global readers owing to the nature of political, economic, and social transition propelled by new experimentation of governance structure.

For setting the context of Nepal’s overall healthcare governance, this paper provides the country context, disaster risk profile, health management system, survey introduction, and key findings of the study in a coherent framework.

Political economy background

Nepal has survived natural, social, economic, and political crises in the past. Situated between the world’s two big economies and populations, China and India, it is accelerating the institutionalization of stable governance and economic development. The political crisis of the recent past, a decade-long armed conflict between 1996-2006, and political maneuvering led to the introduction of a new Constitution in 2015. This Constitution transformed Nepal from a unitary centralized form of governance to a decentralized federal system. It also ended the conventional monarchical system with the adoption of the republic system. This new polity has allocated government business among three tiers- federal, provincial, and local- of government with defined responsibilities (exclusive and concurrent). The new governance arrangements have allowed Nepal to function in a more concerted and complementary way to deal with public problems, with sub-national governments having autonomy in several functions to deal with the issues in their jurisdictions. The governance of Nepal is now managed by 761 governing units (federation, 7 provinces, and 753 local units), each order having defined roles, but overlapping in some cases. Health is an example of such overlap.

With the new governance architecture in place, the three orders of the governments are taking initiatives to implement constitutional mandates. The Constitution safeguards the autonomy of federal units while qualifying the model of intergovernmental relationships based on the principles of ‘cooperation, co-existence, and coordination’. It implies that the federal units have to adhere to the basic principles of cooperative federalism while implementing the constitutional mandates (Dhungana, Pokharel, & Poudel, 2021). Such cooperation may be both formal or informal and vertical or horizontal. For the effective functioning of the federal units, the Constitution and subsequent legal arrangements propose several structural and institutional arrangements for promoting intergovernmental relations including fiscal relations (Pokharel & Sapkota, 2021).

Intergovernmental relations

The theories and literature do not have a universal definition of intergovernmental relations. However, they acknowledge the diversity in basic structures, mechanisms, and institutionalization (Poirier & Saunders, 2010), a common purpose is clear- mechanisms, institutions, and opportunities for interactions among the orders of government. It has mainly two dimensions- structural and functional. While the structural dimension is about the institutional arrangements defined by the policies and laws that provide official space for interactions among the levels of government, the functional perspective assumes to be organic and evolving. The governing units may explore and agree on the areas of cooperation, exchange support and provide the best compliments to deal with the issues of 'interdependencies and spill-over effects due to overlaps in functions and jurisdictions' (McEwen, Petersohn, & Swan, 2015).

The national government may be interested to use coordination mechanisms to make sure that its policies and standards are implemented by the sub-national governments, while the sub-national governments may take it as a space to negotiate power and finance. In an institutionalized system, the defined frameworks and practices provide inputs for intergovernmental relations and are more official in processes and contents. However, there are limits to formal relations. The constitution, legislation, and policies are closed documents while the relationship is fluid and dynamic. To deal with inter-jurisdictional dynamism, informal means of interaction, communication, and engagement are equally important, given that such practices would promote the public interests and are then backed up by a formal process. In the absence of an institutionalized system, the relations are person-centric, ad-hoc, intuitive, and non-transparent. It also lacks accountability among the actors.

As Nepal is at the early stage of institutionalizing the three-tier federal system, assessing the dynamics of intergovernmental relations merits attention for two reasons. First, as Nepal’s federal form of governance is unfolding, it adds value to understanding to what extent the formal structural arrangements of intergovernmental interactions are functional. Second, public health is a shared responsibility among the levels of government, demanding a concerted collaboration among the government spheres. It is worthwhile to weigh and expose gaps in the practice of cooperation and coordination while dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper, therefore, contributes to updating the literature on intergovernmental relations through fresh insights of practices drawing lessons from a country that is undergoing political and governance transition.

Disaster and health pandemic profile

Nepal is also considered a country in the high-risk zone for disasters such as earthquakes, floods, landslides, climate-induced disasters, and health pandemics. The recent earthquake of 2015 claimed the lives of nearly 10,000 people and caused an economic loss of over $7 billion, almost one-third of GDP (National Planning Commission [NPC], 2015). Table 1 shows the major disaster risks in Nepal. In addition, Nepal suffers several disease outbreaks of different scales owing to poor socio-economic status, insufficient health infrastructures, and inefficiency of health governance. For example, in 2009 an outbreak of cholera was identified in over 30,000 people with a casualty of over 500 in a western uphill district of Jajarkot (Bhandari, Dixit, Ghimire, & Maskey, 2010). The district falls into a category of low human development index of the total of 77 districts in the country. A recent outbreak in the mid-western southern plain district of Kapilvastu[1] is another piece of evidence to reiterate that Nepal is in the risk zone of a health epidemic.

Table 1. Disaster Risk Profile of Nepal

Types of hazards |

Nature |

Location |

Reasons of vulnerability |

Landslides |

Recurrent |

The hilly districts of Nepal are located in the Siwalik, Mahabharat range (east-west lower hill range), mid-land, and also fore and higher Himalayas |

Both natural and human factors such as steep slopes, fragile geology, high intensity of rainfall, deforestation, and unplanned human settlements |

Floods |

Most common |

River basins like Koshi (eastern Nepal), Narayani (central), Karnali (mid-western), Mahakali (far-western) rivers perennial rivers |

Anthropogenic activities like improper land use, encroachment into vulnerable land slopes, and unplanned development activities such as the construction of roads and irrigation canals without proper protection measures in the vulnerable mountain belt and climate change |

Glacier lakes outburst floods (GLOFs) |

Occasional |

High altitude areas particularly on the foothill of the mountain |

Damming in by moraines, the lakes contained huge volumes of water melting off the glacier may lead to outbreak the lakes |

Earthquake |

Occasional |

Major active faults in east-west alignment, entire Nepal which lies in active seismic zone |

Siwalik, the lesser Himalaya and frontal part of the Higher Himalaya |

Fire |

Recurrent |

Mid hill areas |

78% of agro-base households, cluster-based houses more susceptible to catching fire, in dry season wild or forest fire |

Drought |

Recurrent |

Some parts of Terai, mid-land and Trans-Himalayan belts of Nepal |

Mostly caused by uneven and irregular low monsoon rainfall and the lack of irrigation facilities further exacerbates the effect of drought causing enormous loss of crops production leading to the shortage and insecurity of food |

Avalanche |

Occasional |

High mountainous region having rugged and steep slopes topographically |

Slopes, the thickness of snow, or human activity with cumulated debris in the snowline. |

Source: Ministry of Home Affairs (MoHA), 2017

Throughout the modern history of healthcare management, Nepal has survived the health crisis that took the lives of hundreds of thousands together with devastating socio-economic impact. These causes of death have differential impacts on the population depending on their socio-economic vulnerabilities (Pokharel & Dahal, 2020). However, in the past two decades, Nepal has made progress in combating the health crisis, thereby improving overall health governance. Between 1 January to 31 December 2021, the following 10 major causes of death are identified in Nepal, excluding natural disasters.

Table 2. Top 10 Causes of Death (health and road safety related) Between 1 January-31 December 2021

Throughout the modern history of healthcare management, Nepal has survived the health crisis that took the lives of hundreds of thousands together with devastating socio-economic impact. These causes of death have differential impacts on the population depending on their socio-economic vulnerabilities (Pokharel & Dahal, 2020). However, in the past two decades, Nepal has made progress in combating the health crisis, thereby improving overall health governance. Between 1 January to 31 December 2021, the following 10 major causes of death are identified in Nepal, excluding natural disasters.

Table 2. Top 10 Causes of Death (health and road safety related) Between 1 January-31 December 2021

Cause |

Number of deaths |

Coronary heart disease |

34,073 |

Stroke |

16,158 |

Lung disease |

13,815 |

Diarrheal diseases |

9,807 |

Influenza and pneumonia |

9,685 |

COVID-19 |

8,880 |

Diabetes mellitus |

6,537 |

Tuberculosis |

6,481 |

Road traffic accidents |

5,101 |

Source: World Life Expectancy, 2022

As displayed in Table 2, Nepal suffers from several health risks. Although the burden of non-communicable diseases is increasing, the contribution of communicable diseases including COVID was significant in the reference period. As communicable diseases transcend physical boundaries, it merits the attention of the orders of the government to strengthen coordination for combating these public health issues.

2. Healthcare governance in Nepal

Policy provisions and challenges of transition

Healthcare governance is one of the largest governance networks in Nepal. In the erstwhile system, the central government led by the Ministry of Health and Population was responsible for policy, regulation, finance, and management of health professionals. Nepal introduced the first fifteen-year long-term health plan in 1975. Much about the implementation status of the plan has been undocumented but evidence shows that the plan was instrumental to develop the foundation of health services in Nepal. Against this backdrop, the first National Health Policy was introduced in 1991, with one of the objectives to develop sub-national health capacity by establishing primary health centers and health posts as the frontline health service organizations. Amidst the criticisms of ineffective implementation of policy, Nepal introduced the second long-term health plan (1997-2017), intending to modernize health services and ensure universal access to healthcare. Following the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in 2015, an updated health policy reflecting the constitutional mandate that recognizes health as a fundamental right has been enforced in 2019.

The 2019 policy considers ‘healthy, alert and conscious citizens oriented to happy life’ as the overarching vision. The policy states to focus on the ‘integrated preparedness and response measures shall be adopted to combat communicable diseases, insect-borne and animal-borne diseases, problems related with climate change, other diseases, epidemics and disasters’ (Ministry of Health and Population [MoHP], 2019). However, the policy fails to address exclusively the intergovernmental dynamics of health crisis management and emergency services. The policy requires it to be updated to address the issues of health crisis management that surfaced during the outbreak of COVID-19.

Considering the wider scope and externalities of health services, the Constitution of Nepal 2015 has assigned health as a shared responsibility among the federal, provincial, and local governments. The division of functions is mainly based on the ‘principle of subsidiarity’ and the corresponding principle of ‘economies of scale’. With these principles, the local governments are mainly responsible for managing the basic health services, preventive measures through promotional activities, disease surveillance, and feeding data to the national system. In addition, they complement and support federal and provincial health programs. The provincial governments, being the medium-order government, are responsible for medium-order health services including provincial health policy, management of health facilities, developing the capacity of local governments, disease surveillance, receiving data from local governments, and feeding to the central database. The federal government, being the higher-order government, is responsible for national health policies, the management of tertiary and referral hospitals, control and management of communicable diseases, health financing, vaccination, and national health campaigns. While there are exclusive competences of levels of government, there are also considerable overlaps in mandates of healthcare services (Acharya, Upadhyay, & Acharya, 2020), creating confusion over sharing of responsibility.

Table 3. Allocation of Health Functions Among Federal, Provincial and Local Level

As displayed in Table 2, Nepal suffers from several health risks. Although the burden of non-communicable diseases is increasing, the contribution of communicable diseases including COVID was significant in the reference period. As communicable diseases transcend physical boundaries, it merits the attention of the orders of the government to strengthen coordination for combating these public health issues.

2. Healthcare governance in Nepal

Policy provisions and challenges of transition

Healthcare governance is one of the largest governance networks in Nepal. In the erstwhile system, the central government led by the Ministry of Health and Population was responsible for policy, regulation, finance, and management of health professionals. Nepal introduced the first fifteen-year long-term health plan in 1975. Much about the implementation status of the plan has been undocumented but evidence shows that the plan was instrumental to develop the foundation of health services in Nepal. Against this backdrop, the first National Health Policy was introduced in 1991, with one of the objectives to develop sub-national health capacity by establishing primary health centers and health posts as the frontline health service organizations. Amidst the criticisms of ineffective implementation of policy, Nepal introduced the second long-term health plan (1997-2017), intending to modernize health services and ensure universal access to healthcare. Following the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in 2015, an updated health policy reflecting the constitutional mandate that recognizes health as a fundamental right has been enforced in 2019.

The 2019 policy considers ‘healthy, alert and conscious citizens oriented to happy life’ as the overarching vision. The policy states to focus on the ‘integrated preparedness and response measures shall be adopted to combat communicable diseases, insect-borne and animal-borne diseases, problems related with climate change, other diseases, epidemics and disasters’ (Ministry of Health and Population [MoHP], 2019). However, the policy fails to address exclusively the intergovernmental dynamics of health crisis management and emergency services. The policy requires it to be updated to address the issues of health crisis management that surfaced during the outbreak of COVID-19.

Considering the wider scope and externalities of health services, the Constitution of Nepal 2015 has assigned health as a shared responsibility among the federal, provincial, and local governments. The division of functions is mainly based on the ‘principle of subsidiarity’ and the corresponding principle of ‘economies of scale’. With these principles, the local governments are mainly responsible for managing the basic health services, preventive measures through promotional activities, disease surveillance, and feeding data to the national system. In addition, they complement and support federal and provincial health programs. The provincial governments, being the medium-order government, are responsible for medium-order health services including provincial health policy, management of health facilities, developing the capacity of local governments, disease surveillance, receiving data from local governments, and feeding to the central database. The federal government, being the higher-order government, is responsible for national health policies, the management of tertiary and referral hospitals, control and management of communicable diseases, health financing, vaccination, and national health campaigns. While there are exclusive competences of levels of government, there are also considerable overlaps in mandates of healthcare services (Acharya, Upadhyay, & Acharya, 2020), creating confusion over sharing of responsibility.

Table 3. Allocation of Health Functions Among Federal, Provincial and Local Level

Federal level |

Provincial level |

Local level |

|

|

|

Source: Summarized from Constitution of Nepal 2015 and related acts

This transformation in health governance was effective from the 2015 Constitution and subsequent elections at local, provincial, and federal levels in 2017. Following the initial level of organizational set-up, Nepal is facing challenges to manage transition together with unclarity in the functional allocations, the complexity of the new system, and the residual impact of the erstwhile system (Pokharel & Sapkota, 2021; Dhungana, Pokharel, & Poudel, 2021), the COVID pandemic imposed additional burden to Nepal’s ongoing transition. Nepal's adventure with the federal system was to be supported by immediate and effective arrangements of policies, legislation, and structures. Although the Constitution provides a broader guideline for business allocation among the orders of government, the centrally managed functions and functionaries were required to transfer to subnational governments through a clearly defined allocation framework.

In the absence of such a framework, there was an unanticipated delay in setting up new arrangements and facilitating the transition. As healthcare governance is one of the major public activities, having a large network of facilities, and financial and human resources, the restructuring was a daunting task. The transition witnessed challenges to ensure uninterrupted health services and medical supplies (Thapa, Bam, Tiwari, Sinha, & Dahal, 2019). While the debates on constitutional mandates versus legacy among federal, provincial, and local governments in ownership and control of health facilities and services were enduring, COVID-19 confronted the wobbling healthcare governance.

Health financing

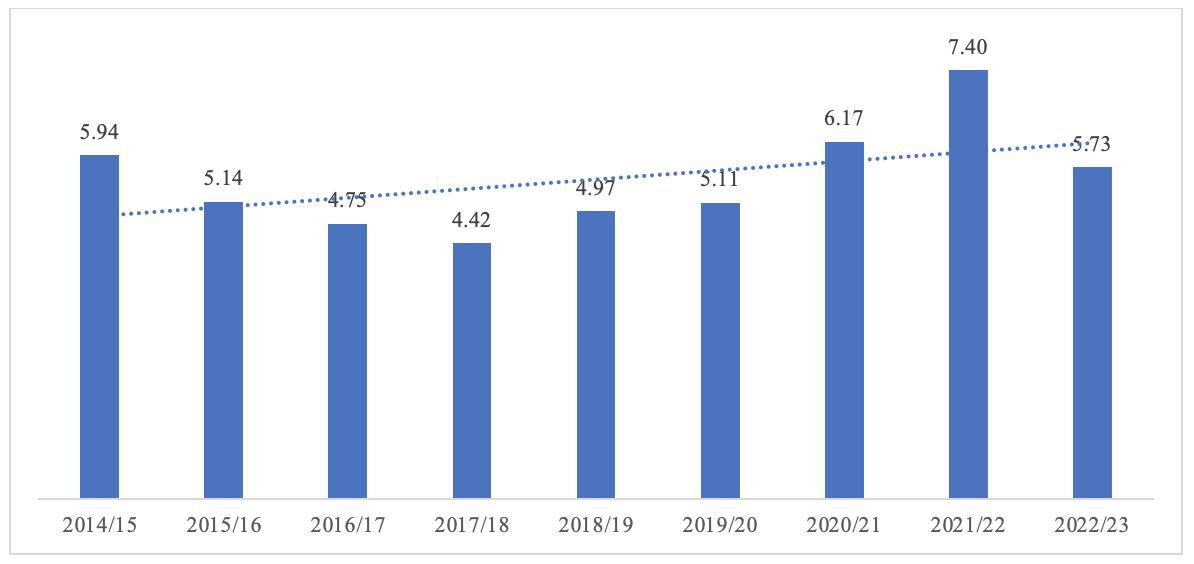

The federal budget is the main source of health sector financing. Nepal's health financing is far less (4.45% of GDP) than the world's average of 9.83% of GDP in 2019 (The World Bank, 2022). Figure 1 shows the allocation percentage in the health sector in the national budget between 2014/15 to 2022/23. The highest allocation in the health sector was in 2021/22, owing to the government's allocation priority to contain COVID, then a reduction in the subsequent year. However, on average, the health sector has received around 5% of the total budget in the last decade, which is far less than the WHO recommendation.

Figure 1. Proportion of Allocation in the Health Sector in the Federal Budget (2014/15-2022/23)

This transformation in health governance was effective from the 2015 Constitution and subsequent elections at local, provincial, and federal levels in 2017. Following the initial level of organizational set-up, Nepal is facing challenges to manage transition together with unclarity in the functional allocations, the complexity of the new system, and the residual impact of the erstwhile system (Pokharel & Sapkota, 2021; Dhungana, Pokharel, & Poudel, 2021), the COVID pandemic imposed additional burden to Nepal’s ongoing transition. Nepal's adventure with the federal system was to be supported by immediate and effective arrangements of policies, legislation, and structures. Although the Constitution provides a broader guideline for business allocation among the orders of government, the centrally managed functions and functionaries were required to transfer to subnational governments through a clearly defined allocation framework.

In the absence of such a framework, there was an unanticipated delay in setting up new arrangements and facilitating the transition. As healthcare governance is one of the major public activities, having a large network of facilities, and financial and human resources, the restructuring was a daunting task. The transition witnessed challenges to ensure uninterrupted health services and medical supplies (Thapa, Bam, Tiwari, Sinha, & Dahal, 2019). While the debates on constitutional mandates versus legacy among federal, provincial, and local governments in ownership and control of health facilities and services were enduring, COVID-19 confronted the wobbling healthcare governance.

Health financing

The federal budget is the main source of health sector financing. Nepal's health financing is far less (4.45% of GDP) than the world's average of 9.83% of GDP in 2019 (The World Bank, 2022). Figure 1 shows the allocation percentage in the health sector in the national budget between 2014/15 to 2022/23. The highest allocation in the health sector was in 2021/22, owing to the government's allocation priority to contain COVID, then a reduction in the subsequent year. However, on average, the health sector has received around 5% of the total budget in the last decade, which is far less than the WHO recommendation.

Figure 1. Proportion of Allocation in the Health Sector in the Federal Budget (2014/15-2022/23)

Source: Collected from annual budget speech (2014/15-2022/23) from Ministry of Finance [MoF] (2022)

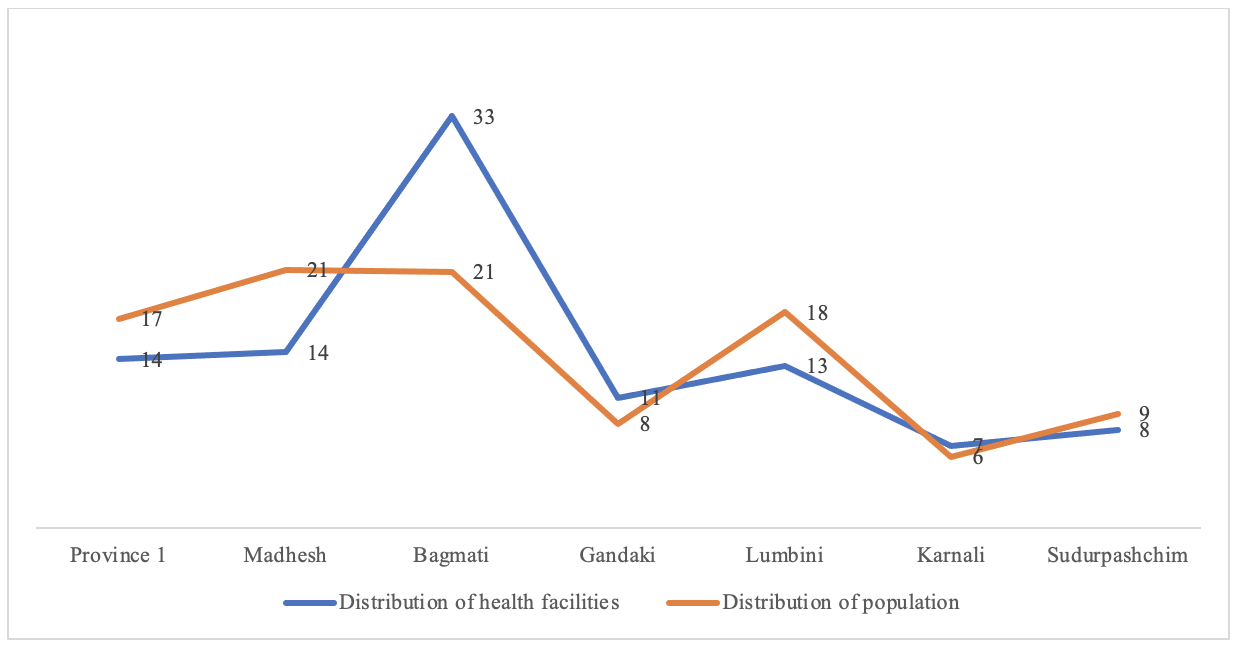

The data of the Department of Health Services shows as of 2017/18 nearly 7,000 health facilities of different types form the institutional structure of health governance. Of these, nearly 30% are private health facilities providing health services throughout the country. However, a noticeable disparity is observed in terms of the distribution of health facilities with the ratio of population distribution. For example, Bagmati Province, which also includes the federal capital, has domination in the distribution of health facilities, with nearly 35% of total health facilities against a one-fifth share of the total population. On the contrary, Madhesh Province holds 14% of health facilities against an equivalent share with Bagmati Province in the total population. This disparity warrants a foreseeable capacity gap in healthcare governance and calls for balancing the distribution of health facilities in response to population distribution.

Figure 2. Distribution of Health Facilities and Population by Provinces of Nepal

The data of the Department of Health Services shows as of 2017/18 nearly 7,000 health facilities of different types form the institutional structure of health governance. Of these, nearly 30% are private health facilities providing health services throughout the country. However, a noticeable disparity is observed in terms of the distribution of health facilities with the ratio of population distribution. For example, Bagmati Province, which also includes the federal capital, has domination in the distribution of health facilities, with nearly 35% of total health facilities against a one-fifth share of the total population. On the contrary, Madhesh Province holds 14% of health facilities against an equivalent share with Bagmati Province in the total population. This disparity warrants a foreseeable capacity gap in healthcare governance and calls for balancing the distribution of health facilities in response to population distribution.

Figure 2. Distribution of Health Facilities and Population by Provinces of Nepal

Source: Ministry of Health and Population [MoHP], (2018); Central Bureau of Statistics (2022)

3. COVID Management: Policies and Institutional Arrangements

The first COVID case in Nepal was detected on 23 January 2020. Following the detection, Nepal saw a slow spread of COVID at the early stage. The peak of the first wave was noticed only in the third week of October 2020, nine months later, with a record of 5,753 cases on 21 October 2020. The second wave emerged in April 2021, which was more devastating than the first wave as observed worldwide. The second wave alone contributed to more than 80% of total infections and 90% of total deaths in Nepal. The COVID positivity rate in the second wave was higher than 2.5 times that of the first wave. For a specific day, the positivity rate in the second wave scaled to over half of the total tests against 35%in the first wave (Ghimire, 2021). The cumulative data shows as of 8 May 2022, Nepal has 978,942 COVID cases with 98.8% recovery and cumulative deaths of 11,952 with a rate of 1.2%.[1] In terms of vaccination, Nepal is mainly dependent on grants, purchases, and the Covax scheme. As of 8 May 2022, almost 66% of the eligible population have received a complete vaccination and 8.9% have full doses, ranking in the 5th position in the SAARC region and seven percentage points higher coverage than the global average[2].

With the detection of the first case and global news of the outbreak including in the neighboring countries, Nepal took official initiatives to combat the pandemic by forming a High-Level Coordination Committee (HLCC) in early March 2020 and made attempts to mobilize all concerned sectors. The HLCC was then made responsible for making decisions and coordination among all the stakeholders including the provincial and local governments. The HLCC was eventually replaced by the COVID-19 Crisis Management Centre (CCMC), which had clear mandates. The CCCM was vertically organized with a similar structure replicated at provincial, district, and municipal levels, but no vertical structural linkages amongst them. The unilateral decisions of CCMC were circulated downward. The sub-national governments were considered passive agencies of the federal decisions.

During the first wave, the government made attempts to address the COVID crisis through executive orders rather than any well-framed legal and policy instruments, while there were several guidelines and procedures introduced to contain the crisis. In the second wave of COVID, the government introduced COVID-19 Crisis Management Ordinance on 20 May 2021, which gave a legal mandate to COVID-19 Crisis Management Centre (CCMC) to take decisions in combating the crisis. However, the ordinance could not get approval from the parliament, reinstating the practices of the decision process to executive orders.

In the early days, the CCMC used to meet regularly, make decisions and resolve issues of coordination, but gradually it became ineffective. The agencies involved in managing COVID started working in their way. The decisions of the CCMC were ignored by the Cabinet and other responsible agencies, making COVID control efforts disintegrated and departmental. The Ministry of Health and Population, the focal agency to deal with public health issues, considered the CCMC as irrelevant and just an additional structure having no functional relevance (Bagale, 2020). The declining effectiveness of the CCMC was mainly due to unclear division of work and undermining of the strengths of the regular structure, particularly of the Ministry of Health and Population. Eventually, the much-overvalued body was considered a burden (Pradhan & Prasain, 2021).

Although the federal government was decisive in managing the COVID crisis, the provincial and local governments were mainly made responsible for public health service delivery, prevention of transmission and epidemiological investigations and tracking, ensuring other public services, and supporting social and relief activities (Mainali, Tosun, & Yilmaz, 2021). In addition, the sub-national governments were made responsible to implement federal orders and deal with public grievances, maintain records of the immigrants and other beneficiaries, distribute relief packages, and promote public health awareness.

4. Local Government and Pandemic Management

This section presents the findings from the survey of the local governments. The survey mainly captures the perspective of the local governments on the dimensions of COVID control activities, financial arrangements, policy, and political coordination among the orders of the governments. For making comparison over the periods, this paper draws results from the Round 1 survey conducted in May-June 2020 (sample of 115 LGs of the 753) and Round 2 survey conducted in October-November 2020 (sample of 115 LGs of the 753), and Round 3 survey conducted in April-May 2021 (census of all 753 LGs). The samples LGs in Round I and Round II were a replication of the Federalism Capacity Needs Assessment study conducted by Georgia State University and Nepal Administrative Staff College for the Government of Nepal in 2019.[1] The study used multi-stage stratified random sampling to make the sample representative of Nepal’s local governments, while Round 3 was a census of all local governments. The survey respondents were the elected chiefs (mayor of urban municipality and chairperson of the rural municipality), deputy chief, and chief administrative officer of the local governments. This paper uses responses from the elected chiefs only. This survey was jointly conducted by a team of Yale Economic Growth Center, London School of Economics and Political Sciences, Governance Lab and Nepal Administrative Staff College. Data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire that was administered through telephone interviews in a strictly regulated protocol.

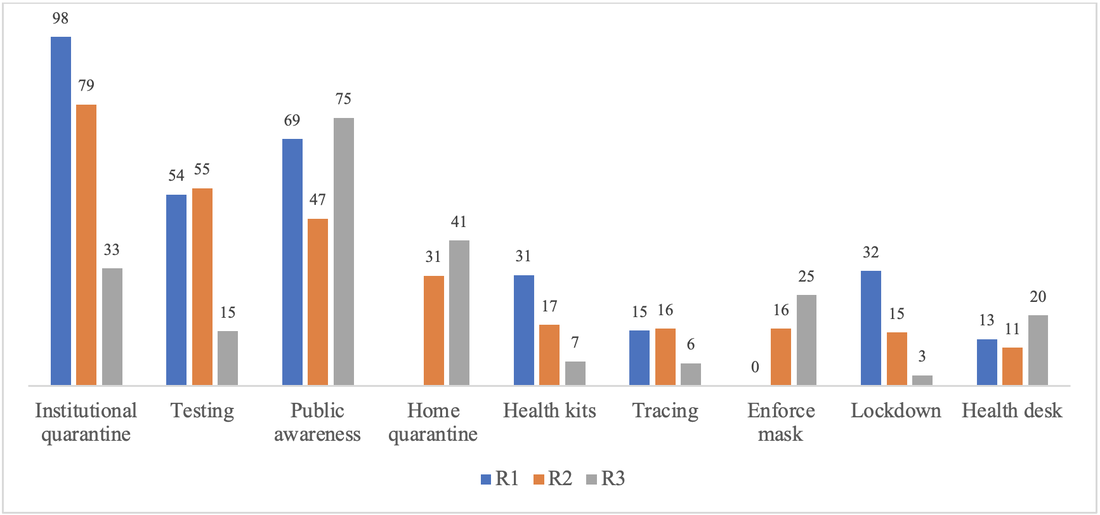

How did local governments respond to COVID?

Local governments have been involved in several public health activities of preventive and curative services. Management of quarantine, testing, tracing, management of home quarantine, distributing health kits, enforcing a mask and other social measures, lockdown, and health desk were the major activities that local governments identified themselves that they were involved with. In the first round (May-June 2020), the local governments were actively involved in the management of quarantine (97.6%), public awareness (69.0%), and testing (53.6%). By October-November 2020, a decline in the engagement of local governments in some COVID-containing activities was observed. For example, 79% of local governments said to have been engaged in quarantine, 20 percentage points less than earlier round, while 55% were engaged in testing, slightly higher than the earlier round, and involvement in public awareness was reduced to 47%, almost 20 percentage points less than the earlier round. Importantly, management of home quarantine emerged as a new function as 31% of local governments reported to have been engaged to manage it. Likewise, enforcement of masks was an emerging priority for 16% of local governments, while 15% of local governments said to have been actively engaged in enforcing lockdown, almost 16 percentage points less than the earlier round.

The third round of the survey, corroborating the second wave of COVID, showed a different trend in the engagement of local governments. Engagement in management of institutional (a public center) quarantine further declined to 33%, testing had a sharp decline to 15%, while engagement in public awareness increased to 75%, management of home quarantine increased to 41%, 10 percentage points higher than the second round. Likewise, enforcement of masks (25.4%) and management of health desk (19.7%) were other priorities for the local governments.

In addition, management of schools, COVID hospitals, ambulance services, implementing social distancing, and administering vaccines were other emerging activities that local governments were found to be involved in the wake of the second wave.

Figure 3. Activities of Local Governments in COVID response (R1, R2, and R3)

3. COVID Management: Policies and Institutional Arrangements

The first COVID case in Nepal was detected on 23 January 2020. Following the detection, Nepal saw a slow spread of COVID at the early stage. The peak of the first wave was noticed only in the third week of October 2020, nine months later, with a record of 5,753 cases on 21 October 2020. The second wave emerged in April 2021, which was more devastating than the first wave as observed worldwide. The second wave alone contributed to more than 80% of total infections and 90% of total deaths in Nepal. The COVID positivity rate in the second wave was higher than 2.5 times that of the first wave. For a specific day, the positivity rate in the second wave scaled to over half of the total tests against 35%in the first wave (Ghimire, 2021). The cumulative data shows as of 8 May 2022, Nepal has 978,942 COVID cases with 98.8% recovery and cumulative deaths of 11,952 with a rate of 1.2%.[1] In terms of vaccination, Nepal is mainly dependent on grants, purchases, and the Covax scheme. As of 8 May 2022, almost 66% of the eligible population have received a complete vaccination and 8.9% have full doses, ranking in the 5th position in the SAARC region and seven percentage points higher coverage than the global average[2].

With the detection of the first case and global news of the outbreak including in the neighboring countries, Nepal took official initiatives to combat the pandemic by forming a High-Level Coordination Committee (HLCC) in early March 2020 and made attempts to mobilize all concerned sectors. The HLCC was then made responsible for making decisions and coordination among all the stakeholders including the provincial and local governments. The HLCC was eventually replaced by the COVID-19 Crisis Management Centre (CCMC), which had clear mandates. The CCCM was vertically organized with a similar structure replicated at provincial, district, and municipal levels, but no vertical structural linkages amongst them. The unilateral decisions of CCMC were circulated downward. The sub-national governments were considered passive agencies of the federal decisions.

During the first wave, the government made attempts to address the COVID crisis through executive orders rather than any well-framed legal and policy instruments, while there were several guidelines and procedures introduced to contain the crisis. In the second wave of COVID, the government introduced COVID-19 Crisis Management Ordinance on 20 May 2021, which gave a legal mandate to COVID-19 Crisis Management Centre (CCMC) to take decisions in combating the crisis. However, the ordinance could not get approval from the parliament, reinstating the practices of the decision process to executive orders.

In the early days, the CCMC used to meet regularly, make decisions and resolve issues of coordination, but gradually it became ineffective. The agencies involved in managing COVID started working in their way. The decisions of the CCMC were ignored by the Cabinet and other responsible agencies, making COVID control efforts disintegrated and departmental. The Ministry of Health and Population, the focal agency to deal with public health issues, considered the CCMC as irrelevant and just an additional structure having no functional relevance (Bagale, 2020). The declining effectiveness of the CCMC was mainly due to unclear division of work and undermining of the strengths of the regular structure, particularly of the Ministry of Health and Population. Eventually, the much-overvalued body was considered a burden (Pradhan & Prasain, 2021).

Although the federal government was decisive in managing the COVID crisis, the provincial and local governments were mainly made responsible for public health service delivery, prevention of transmission and epidemiological investigations and tracking, ensuring other public services, and supporting social and relief activities (Mainali, Tosun, & Yilmaz, 2021). In addition, the sub-national governments were made responsible to implement federal orders and deal with public grievances, maintain records of the immigrants and other beneficiaries, distribute relief packages, and promote public health awareness.

4. Local Government and Pandemic Management

This section presents the findings from the survey of the local governments. The survey mainly captures the perspective of the local governments on the dimensions of COVID control activities, financial arrangements, policy, and political coordination among the orders of the governments. For making comparison over the periods, this paper draws results from the Round 1 survey conducted in May-June 2020 (sample of 115 LGs of the 753) and Round 2 survey conducted in October-November 2020 (sample of 115 LGs of the 753), and Round 3 survey conducted in April-May 2021 (census of all 753 LGs). The samples LGs in Round I and Round II were a replication of the Federalism Capacity Needs Assessment study conducted by Georgia State University and Nepal Administrative Staff College for the Government of Nepal in 2019.[1] The study used multi-stage stratified random sampling to make the sample representative of Nepal’s local governments, while Round 3 was a census of all local governments. The survey respondents were the elected chiefs (mayor of urban municipality and chairperson of the rural municipality), deputy chief, and chief administrative officer of the local governments. This paper uses responses from the elected chiefs only. This survey was jointly conducted by a team of Yale Economic Growth Center, London School of Economics and Political Sciences, Governance Lab and Nepal Administrative Staff College. Data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire that was administered through telephone interviews in a strictly regulated protocol.

How did local governments respond to COVID?

Local governments have been involved in several public health activities of preventive and curative services. Management of quarantine, testing, tracing, management of home quarantine, distributing health kits, enforcing a mask and other social measures, lockdown, and health desk were the major activities that local governments identified themselves that they were involved with. In the first round (May-June 2020), the local governments were actively involved in the management of quarantine (97.6%), public awareness (69.0%), and testing (53.6%). By October-November 2020, a decline in the engagement of local governments in some COVID-containing activities was observed. For example, 79% of local governments said to have been engaged in quarantine, 20 percentage points less than earlier round, while 55% were engaged in testing, slightly higher than the earlier round, and involvement in public awareness was reduced to 47%, almost 20 percentage points less than the earlier round. Importantly, management of home quarantine emerged as a new function as 31% of local governments reported to have been engaged to manage it. Likewise, enforcement of masks was an emerging priority for 16% of local governments, while 15% of local governments said to have been actively engaged in enforcing lockdown, almost 16 percentage points less than the earlier round.

The third round of the survey, corroborating the second wave of COVID, showed a different trend in the engagement of local governments. Engagement in management of institutional (a public center) quarantine further declined to 33%, testing had a sharp decline to 15%, while engagement in public awareness increased to 75%, management of home quarantine increased to 41%, 10 percentage points higher than the second round. Likewise, enforcement of masks (25.4%) and management of health desk (19.7%) were other priorities for the local governments.

In addition, management of schools, COVID hospitals, ambulance services, implementing social distancing, and administering vaccines were other emerging activities that local governments were found to be involved in the wake of the second wave.

Figure 3. Activities of Local Governments in COVID response (R1, R2, and R3)

R1= First round of survey between May-June 2020 (sample of 115 LGs)

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample of 115 LGs)

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (all 753 LGs)

Such a shift in activities of the local governments could be attributed to evolving nature of the pandemic- from preventive to curative. In the first wave, the focus was on prevention, where the local governments could play significant roles through quarantine, public awareness, and other social measures. In the second wave of COVID, the demand for curative services received higher priority, which was beyond the capacity and jurisdictions of the local governments. Further, asthe COVID pandemic prolonged, people applied health measures on their own, particularly in testing, quarantine, and other social measures.

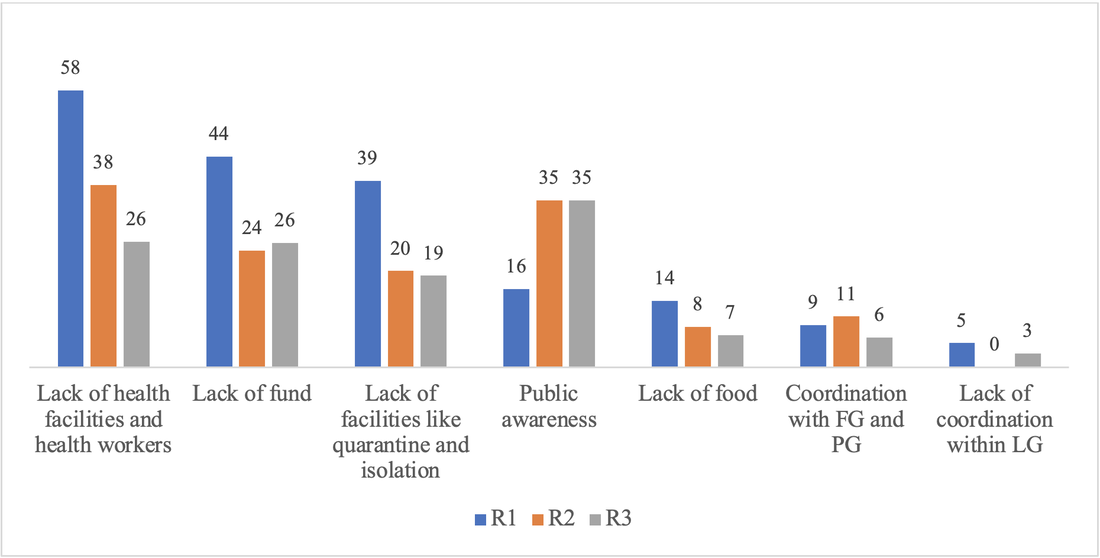

Challenges faced by local governments in dealing with COVID

Further comparative analysis of challenges faced by the local governments to contain COVID shows a varied response over the periods. Inadequate health facilities and health workers were the common challenges that local governments identified throughout but in a declining trend. Noticeably, a decline in the proportion of LGs reporting a lack of health facilities and health workers was recorded at 20 percentage points between round 1 and round 2, and a further decline of 12 percentage points between round 2 and round 3. It may be because, during the crisis, the governments made interventions to improve health facilities, particularly in the expansion of testing centers, upgradation of health facilities, increasing the number of health workers, declaring COVID-specific hospitals, among others. Over the periods, health professionals extended their capacities, they were trained and motivated to deal with the crisis, the social stigma that was alarming at an early stage (Singh & Subedi, 2020) gradually disappeared, and health professionals’ capacity to cope with emergencies improved.

Figure 4. Challenges Faced by the Local Governments in Dealing with COVID

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample of 115 LGs)

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (all 753 LGs)

Such a shift in activities of the local governments could be attributed to evolving nature of the pandemic- from preventive to curative. In the first wave, the focus was on prevention, where the local governments could play significant roles through quarantine, public awareness, and other social measures. In the second wave of COVID, the demand for curative services received higher priority, which was beyond the capacity and jurisdictions of the local governments. Further, asthe COVID pandemic prolonged, people applied health measures on their own, particularly in testing, quarantine, and other social measures.

Challenges faced by local governments in dealing with COVID

Further comparative analysis of challenges faced by the local governments to contain COVID shows a varied response over the periods. Inadequate health facilities and health workers were the common challenges that local governments identified throughout but in a declining trend. Noticeably, a decline in the proportion of LGs reporting a lack of health facilities and health workers was recorded at 20 percentage points between round 1 and round 2, and a further decline of 12 percentage points between round 2 and round 3. It may be because, during the crisis, the governments made interventions to improve health facilities, particularly in the expansion of testing centers, upgradation of health facilities, increasing the number of health workers, declaring COVID-specific hospitals, among others. Over the periods, health professionals extended their capacities, they were trained and motivated to deal with the crisis, the social stigma that was alarming at an early stage (Singh & Subedi, 2020) gradually disappeared, and health professionals’ capacity to cope with emergencies improved.

Figure 4. Challenges Faced by the Local Governments in Dealing with COVID

R1= First round of survey between May-June 2020 (sample 115)

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample 115)

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (sample 753)

Other prominent challenges facing local governments were lack of funds, lack of facilities like quarantine and isolation, public awareness, lack of food for needy and vulnerable populations, and coordination with the federal and provincial governments. All challenges, as perceived by the local governments are on a declining trend but public awareness was on the increasing trend, indicating that educating the public was a challenge, having the cross-sectional impact of such apathy. Studies have shown considerable gaps between knowledge and practice of public safety measures, with lower practice against higher knowledge (Nepal Health Research Council [NHRC], 2020; Sah et al., 2022). Managing public movements at the borders and returnees has been an enduring challenge as Nepal has open and porous borders with India. It is estimated that over five million Nepalis are living in India while nearly one million Indians are in Nepal. The poorly regulated and sub-standard borders of Nepal and India are always busy for both entry and exit. The local governments, particularly adjoining Indian territory, confronted challenges to managing returnees. In addition, the local governments considered the distribution of vaccines as an emerging challenge in the third round.

Support and coordination with federal and provincial governments

A pandemic, such as COVID has an inter-jurisdictional spillover effect and requires competent intergovernmental support and coordination. Such collaboration would improve the enforcement of policy measures, delivery of services, and addressing public demands. However, the results show that in the perception of local governments, such support and coordination were largely insufficient. Important to note is that the local governments perceived that support and coordination have declined over the periods.

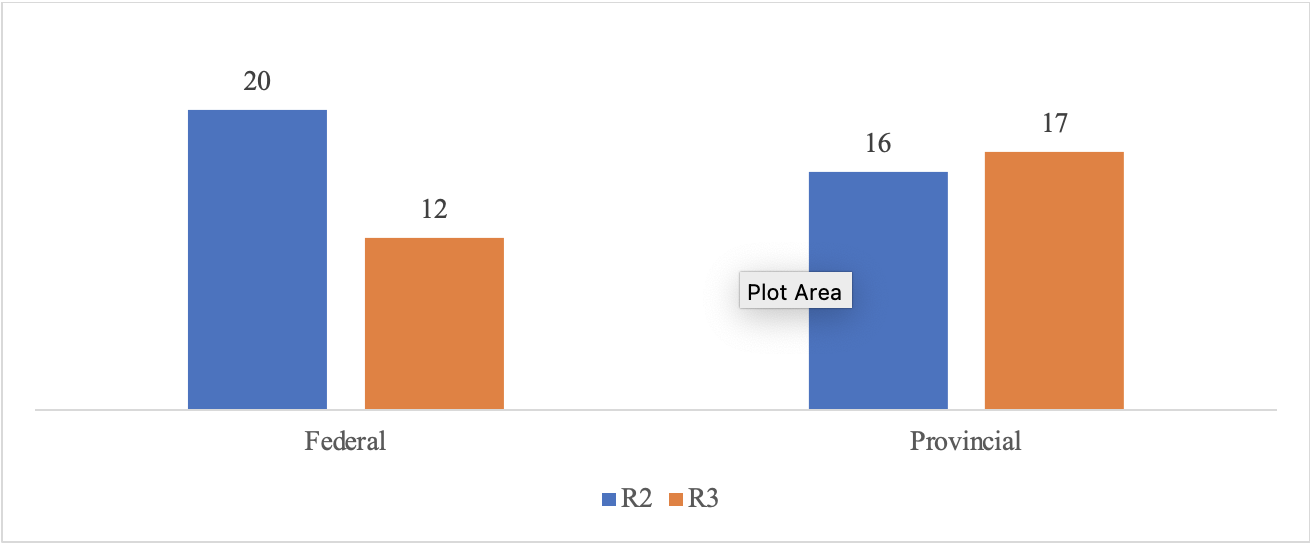

The support includes policy, financial, technical, and human resources while the coordination is more about information flow and decision process. In round 2, one-fifth of local governments considered the support from the federal government adequate while only 16% of local governments perceived so for the provincial governments. The proportion of the local governments considering adequate federal support further declined by eight percentage points in round 3, while it had a marginal increase with the provincial governments.

Figure 5. Proportion of Local Governments Reporting Adequate Support from Federal and Provincial Governments

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample 115)

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (sample 753)

Other prominent challenges facing local governments were lack of funds, lack of facilities like quarantine and isolation, public awareness, lack of food for needy and vulnerable populations, and coordination with the federal and provincial governments. All challenges, as perceived by the local governments are on a declining trend but public awareness was on the increasing trend, indicating that educating the public was a challenge, having the cross-sectional impact of such apathy. Studies have shown considerable gaps between knowledge and practice of public safety measures, with lower practice against higher knowledge (Nepal Health Research Council [NHRC], 2020; Sah et al., 2022). Managing public movements at the borders and returnees has been an enduring challenge as Nepal has open and porous borders with India. It is estimated that over five million Nepalis are living in India while nearly one million Indians are in Nepal. The poorly regulated and sub-standard borders of Nepal and India are always busy for both entry and exit. The local governments, particularly adjoining Indian territory, confronted challenges to managing returnees. In addition, the local governments considered the distribution of vaccines as an emerging challenge in the third round.

Support and coordination with federal and provincial governments

A pandemic, such as COVID has an inter-jurisdictional spillover effect and requires competent intergovernmental support and coordination. Such collaboration would improve the enforcement of policy measures, delivery of services, and addressing public demands. However, the results show that in the perception of local governments, such support and coordination were largely insufficient. Important to note is that the local governments perceived that support and coordination have declined over the periods.

The support includes policy, financial, technical, and human resources while the coordination is more about information flow and decision process. In round 2, one-fifth of local governments considered the support from the federal government adequate while only 16% of local governments perceived so for the provincial governments. The proportion of the local governments considering adequate federal support further declined by eight percentage points in round 3, while it had a marginal increase with the provincial governments.

Figure 5. Proportion of Local Governments Reporting Adequate Support from Federal and Provincial Governments

R1= First round of survey between May-June 2020 (sample 115). This question was not asked in round 1.

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample 115)

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (sample 753)

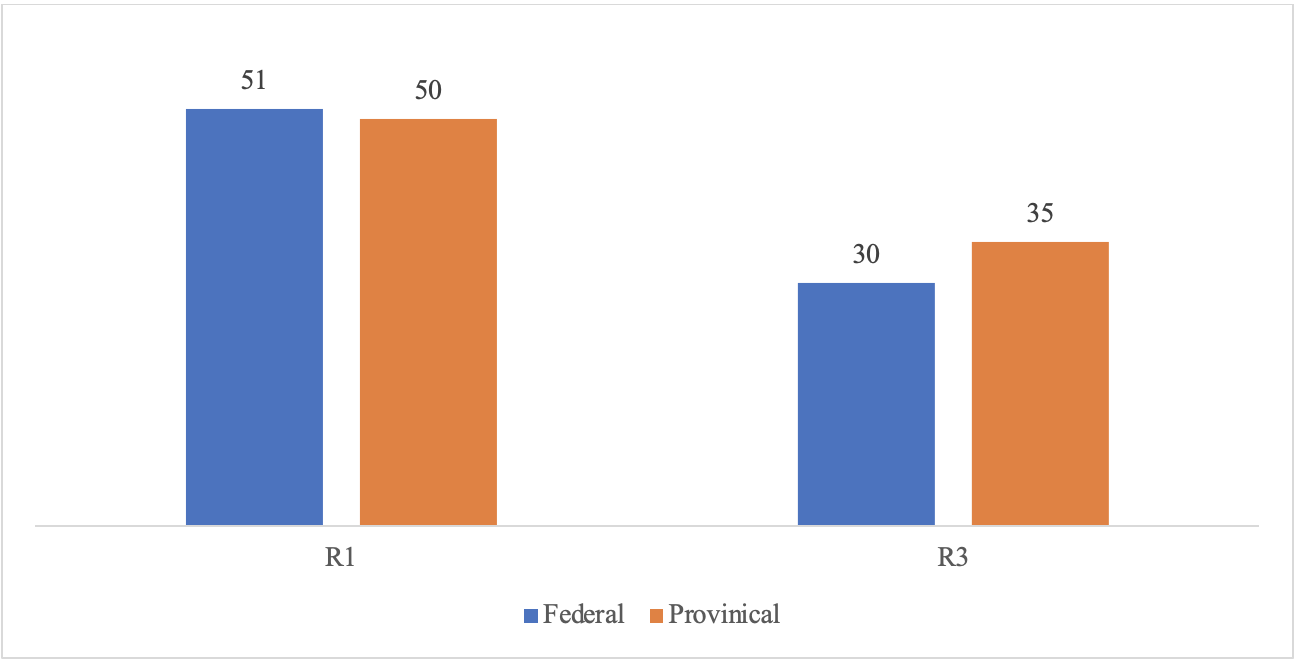

Similar, but relatively better for coordination compared to support, a serious gap in terms of intergovernmental coordination was observed. In round 1, almost half of the local governments perceived enough coordination with the federal and provincial governments, which declined dramatically in round 3 with 21 percentage points for the federal government and 15 percentage points for the provincial governments. Such a gap in the coordination may have negatively impacted the overall performance of managing the crisis.

Figure 6. Proportion of Local Governments Reporting Enough Coordination with the Federal and Provincial Governments

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample 115)

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (sample 753)

Similar, but relatively better for coordination compared to support, a serious gap in terms of intergovernmental coordination was observed. In round 1, almost half of the local governments perceived enough coordination with the federal and provincial governments, which declined dramatically in round 3 with 21 percentage points for the federal government and 15 percentage points for the provincial governments. Such a gap in the coordination may have negatively impacted the overall performance of managing the crisis.

Figure 6. Proportion of Local Governments Reporting Enough Coordination with the Federal and Provincial Governments

R1= First round of survey between May-June 2020 (sample 115).

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample 115). This question was not asked in round 2.

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (sample 753)

In addition, 35% of local governments in round 2 expressed some sort of disagreement in the ways that the federal government took decisions to deal with COVID, particularly in the issues of financing, lockdown, testing, tracing, quarantine, distribution of relief, and vaccines. The proportion of local governments reporting disagreement with the provincial government was slightly less than 30%. These disagreements were mainly in the way the federal government made decisions, the federal policies on lockdown, disproportionate sharing of financial resources (Bhandari, et al., 2020), medical support, distribution of medical supplies and vaccines, and deployment of health professionals. Sub-national governments have mainly criticized the tendency of unilateral decisions of the federal government to ignore the local context and requirements (Mainali, Tosun, & Yilmaz, 2021; Ghimire, 2021). The major deficit in pandemic control was the absence of the federal pandemic act. The CO VID response has been guided by the Infectious Disease Act 1964, the act which was functional in the erstwhile unitary system has been unresponsive to the federal structure. The Act does not recognize the roles of provincial and local governments but mandates agencies of the central government to exercise authority. Although the federal government introduced the COVID control ordinance in 2021, it failed to receive parliamentary approval, pushing COVID control back to half a century-old legislature, and causing lapses in intergovernmental relations.

On the other side, the inept functioning of provincial and local governments was equally responsible for ineffective vertical and horizontal coordination. Despite having low capacity, the local governments, as the first responder, played a relatively better role to contain the health crisis. The provincial governments, the medium order government having responsibility for providing leadership to local governments within their jurisdictions and negotiating with the federal government for effective delivery and leveraging backstopping for local governments and also having ownership of medium order hospitals, were largely criticized for their ineffective roles.

As Nepal's federal system is in its infancy, the structural arrangements to promote intergovernmental relations are yet to be institutionalized. Some coordination mechanisms such as the Inter-Provincial Council, National Coordination Councils, and other structures of coordination are provisioned in the Constitution and subsequent legislations, nonetheless, they are largely dysfunctional (Pokharel & Sapkota, 2021). The CCMC, a top-notch body to lead crisis management, did not have formal space for the participation of sub-national governments. The federal government took unilateral decisions on every aspect of containing COVID and circulated those decisions downward. In most of the cases, the coordination was at the bureaucratic level. The federal government did not realize that the province and local governments were two years younger than the 2015 Constitution and they require constructive support in developing institutional capacity.

One important exogenous factor to reveal here was the protracted political in-fighting in the ruling party. Unrelated but concurrently with the upward surge in virus spread, the internal conflict in the ruling party was triumphing. It distracted the focus of political leaders including the Cabinet members for managing party conflict, thereby plummeting attention on COVID management (Shakya, 2020; Acharya & Thapa, 2021). Such political maneuvering led to a critical deficit in providing effective leadership by the federal government to the sub-national governments. The federal government faced instability, the parliament was dissolved repeatedly while the Supreme Court had to step in to defy the parliament dissolution and the provincial governments also saw the impact of national political maneuvering. The political tug-of-war impeded the coordinated functioning of the government as the top leadership had a priority on reformation of the government than managing the health crisis (Pandey, 2021). Amidst the pandemic mayhem, the factions of the ruling party organized several mass-gathering for influencing the other factions of the party. Such gatherings undermined the health safety measures- further increasing the risk of virus spread. The completely overlooked aspect was the engagement of leaders, who were also holding the executive responsibility, in pleasing their cadres, leaving executive priority almost suspended. At the time when the country needed national unity, and friendly dialogue among political actors and other stakeholders, the collaborative culture was almost non-existence.

Considering the externality of the pandemic, a few local governments spontaneously attempted horizontal partnerships in preparing quarantine centers, enhancing testing facilities, providing relief and medical care, and ensuring safety in public mobility. However, these initiatives were not systematic and not guided by a policy framework.

Coordination meeting

In round 2, the survey captured the number of meetings that local governments conducted with the federal government, provincial government, district administration office, and ward offices on the issues to combat COVID. Frequent meetings were conducted with the ward offices within the jurisdiction of local governments (88.8% said to have 1 to 5 meetings), followed by the district administration office (82.2% said to have 1 to 5 meetings), a federal government’s local agency.

On the contrary, the proportion of local governments reporting not having any meeting with the federal government was 57% and with the provincial government, it was 60%.

Table 4. Frequency of Coordination Meeting

R2= Second round of survey between October-November 2020 (sample 115). This question was not asked in round 2.

R3= Third round of survey between April-May 2021 (sample 753)

In addition, 35% of local governments in round 2 expressed some sort of disagreement in the ways that the federal government took decisions to deal with COVID, particularly in the issues of financing, lockdown, testing, tracing, quarantine, distribution of relief, and vaccines. The proportion of local governments reporting disagreement with the provincial government was slightly less than 30%. These disagreements were mainly in the way the federal government made decisions, the federal policies on lockdown, disproportionate sharing of financial resources (Bhandari, et al., 2020), medical support, distribution of medical supplies and vaccines, and deployment of health professionals. Sub-national governments have mainly criticized the tendency of unilateral decisions of the federal government to ignore the local context and requirements (Mainali, Tosun, & Yilmaz, 2021; Ghimire, 2021). The major deficit in pandemic control was the absence of the federal pandemic act. The CO VID response has been guided by the Infectious Disease Act 1964, the act which was functional in the erstwhile unitary system has been unresponsive to the federal structure. The Act does not recognize the roles of provincial and local governments but mandates agencies of the central government to exercise authority. Although the federal government introduced the COVID control ordinance in 2021, it failed to receive parliamentary approval, pushing COVID control back to half a century-old legislature, and causing lapses in intergovernmental relations.

On the other side, the inept functioning of provincial and local governments was equally responsible for ineffective vertical and horizontal coordination. Despite having low capacity, the local governments, as the first responder, played a relatively better role to contain the health crisis. The provincial governments, the medium order government having responsibility for providing leadership to local governments within their jurisdictions and negotiating with the federal government for effective delivery and leveraging backstopping for local governments and also having ownership of medium order hospitals, were largely criticized for their ineffective roles.