Asian Review for Public Administration (ARPA)

Open Access | Research Article | First published online December 20, 2023

Vol. 31, Nos. 1&2 (January 2020-December 2023)

Dilemmas of Policy Response during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh

Shuvra Chowdhury, Sajib Kumar Roy, Dabjani Saha, Aria Ashraf Anushakha, Asif All Mahmud Akash

Shuvra Chowdhury, Sajib Kumar Roy, Dabjani Saha, Aria Ashraf Anushakha, Asif All Mahmud Akash

"Cite article"Chowdhury, S., Roy, S., Saha, D., Anushakha, A., & Akash, A. (2020-2023). Dilemmas of Policy Response During COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of the University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Asian Review for Public Administration, Vol. 31, Nos. 1&2, 100-119. |

| ||

Abstract: The task of a tertiary-level educational institution is knowledge creation. It is necessary to meet the demands of the changing time and situations. What is the state of the tertiary-level educational institute during a pandemic? How did the authority face the challenges and respond to the policy decision taken by the government? This article followed a case-oriented qualitative research strategy, used empirical data, and followed both primary and secondary sources. It analyzed the dilemmas of policy response of the University of Rajshahi. This study found mixed results. The online teaching-learning process kept the students engaged with their academic activities, teachers completed the courses on time, and maintained communication between students and teachers. However, considering the contextual challenges including the socioeconomic-psychological profile of the students and the incapacity of conducting online teaching, this article recommended some areas for further research.

Keywords: policy response, COVID-19 pandemic, policy process, tertiary-level education

Keywords: policy response, COVID-19 pandemic, policy process, tertiary-level education

Introduction

Higher education institutions create and recreate knowledge. These institutions facilitate the development of competencies and skills, foster creative thinking, and utilize and synthesize new knowledge. They help improveleadership abilities and problem-solving approaches in special areas and develop analytical ability. Thus, higher education institutions ultimately contribute to human development (Jahan, 2015; University Grants Commission of Bangladesh [UGC], 2018; Immanuel, 1996). Higher education can be instrumental in restoring the connections among multiple issues like education, knowledge, wisdom, democratic values, social transformation, etc. (Giroux, 2009). In the transition from an industrialized society to a knowledge-based society, higher education has a vital role in preparing the young generation by providing training with problem-oriented learning, which has an ultimate impact on the economy and society (UGC, 2018). Tertiary education provides an avenue for collaborative research to boost the competitiveness and creativity of the industry, which are essential for the overall development of any country (Rahman et al., 2019). The demographic dividend could bring higher economic growth by fostering digital and technological innovations (Zaman & Sarker, 2021). In the party manifesto of the present ruling party in Bangladesh, the Awami League, the digital government agenda received enormous importance as manifested in the numerous plans and projects under this agenda (Himel & Chowdhury, 2022). However, research studies argue that these innovations are more rhetoric than reality, with the quantity and quality ofdigital innovations needing further improvement as these innovations faced numerous challenges in their implementation(Chowdhury, 2018; Sappru & Sappru, 2014).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as a part of controlling virus proliferation, all types of educational institutes remained closed in Bangladesh. There are three levels in the existing education structure of Bangladesh, i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary (Ali & Subramaniam, 2010). In Bangladesh, the Ministry of Education (MoE) and the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoP&ME) supervise and administer the education system in collaboration with affiliated directorates and departments and a diverse range of self-governing entities. The University Grants Commission of Bangladesh (UGC) is responsible to supervise both the public and private universities as well as the allocation of government grants to these educational institutions. According to the 47th Annual Report 2020 of the UGC, the total number of public and private universities in Bangladesh is 157, as of 31 December 2020. Out of these, 50 are public universities and 107 are private universities (UGC, 2021). Instead of classroom-based traditional in-person learning approaches, the universities in Bangladesh started to conduct online classes to curb the spread of coronavirus while still continuing teaching and learning activities. The process, however, had to face several challenges in a developing country like Bangladesh, such as learners’ inaccessibility to online classes due to financial constraints, low internet connectivity, high internet cost, connectivity problems, etc. (Al-Amin et al., 2021; Panday, 2020).

Based on the above discussion, this article aimed to investigate the difficulties faced by both the students and the authority of tertiary-level educational institutions concerning the COVID-19 epidemic. What initiatives were taken during the lockdown and after? What is the state of the teaching-learning environment at the University of Rajshahi (RU)? What were the problems faced by the administrative authority and the students as well and why?

Methodological issues and data collection tools

Since the subject matter of the research is a contemporary phenomenon and answers “how” “what” and “why” type of questions, this study followed a case-oriented qualitative approach (Chowdhury, 2019; Yin, 2004; Bryman, 2001; Babbie, 2004). Based on both the primary and secondary sources of data, this paper analyzed the dilemmas of policy response regarding the tertiary-level educational institutions in Bangladesh. Since many public universities in Bangladesh have separate laws and regulations, the case of RU was selected for extensive analysis. RU, which has 59 departments, is one of four universities in Bangladesh where the authorities can make decisions on their own as per a 1973 ordinance. It has a total of over 38,000 students (The Daily Prothom Alo, 2022). Data for the case study has been drawn from a total of tenkey informant interviews (KII) of administrative and academic staff. Two focus group discussions (FGD)—one among the male students and another among the female students of the Department of Public Administration of RU—were conducted. The secondary sources included content analysis of newspapers, open data on the website of the university, published journal articles, etc.

This article has a total of six sections. The first section is a discussion of the background of the paper. The second segment is on the development of a theoretical framework and a discussion on the framework of the policy process model. With regard to the objective of the paper, the third section gave an overview of the existing decisions of RU officials and the state of teaching and learning with a broader perspective to understand the dilemmas specifically. The fourth section analyzed the empirical data drawn from KIIs and FGDs, and then followed by data substantiation from published articles. The discussion section provides the actual understanding of the outcome based on the policy framework. The conclusion section offers further research agenda.

Theoretical framework: An analysis of the policy process model

In the early 1970s, public policy practitioners analyzed public policy through the application of formal and mathematical methods to solve the problems of the public sector. It is a field to discuss the interrelation between the government and the beneficiary client. There are two approaches to analyze government policies. First is policy analysis, which tries to solve problems using mathematical and statistical models. The second approach is political public policy, which is concerned with the consequences or outcomes of public policies on health, social welfare, education, and the environment, other than the application of statistical methodologies. Anderson (1997) defines public policy as the "relationship of a government unit to its environment" (cited in Wilson et al., 2020, p. 125). Anderson sees public policy as a tool that governments employ to build strategies and processes for tackling social issues in a specific setting. In the context of the study of policymaking and implementation in public administration, policy denotes the guidance for action. It may take the form of a declaration of guiding principles; a declaration of definite course of action; and a program of activities (Sappru, 1994, p. 133). Policy, planning, and decision-making are three different concepts with underlying different connotations. The scope of the concept of “policy” has a wider connotation, whereas planning has a limited scope. On the other hand, the process of decision-making is concentrated on the issues that are important to achieve planned goals. Policy means a course or principle of action adopted or proposed by an organization or individual, while planning generally refers to the process of thinking about and organizing the activities necessary to attain the intended outcome. Decision-making is described as a method of choosing the best and most effective plan of action from a set of two or more options for achieving the desired result.

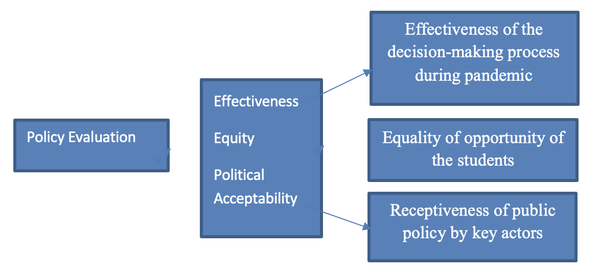

There are many theories and related concepts in the policy process studies—from identifying issues to implementing policies. There is no specific model applicable to all types of policy analysis. The policy analysis model of Patton and Sawicki (1986) gave us an idea about how policy analysts should follow some steps to take a policy and make a decision. The strength of this model is that it provides guidelines for dealing with a particular policy problem as well as prepares a suitable alternative solution to resolve the problem. The first step of this model includes verifying, identifying, and detailing the problem. because it seems challenging to define problems in broader areas of the public policy arena like education, health, or public welfare. Again, the statement of the problem should identify specific problems, focus on acentral issue, and include only critical factors rather than dwelling on unnecessary issues. The analyst must be efficient in preparing a detailed statement of the policy problem and estimating the time and resources for future courses of action. Effectiveness, equity, and political acceptability are three important dimensions in the second phase for establishing evaluation criteria. Identifying alternative policies, evaluating the policies, displaying and distinguishing alternative policies, and monitoring the implemented policy are several other steps that are followed by the policy analyst in the next phase. There are many studies relating to policy formulation and policy implementation processes. Considering the study objective, this paper analyzed the second step of this policy process model: the evaluation criteria of the policy decision (Figure 1).

Effectiveness, equity, and political acceptability are factors that are used in the evaluation criteria for analyzing policies to be taken to address a given problem. Effectiveness refers to the outcome of the intended objective of the policy. This paper deals with the issue of effectiveness during a crisis, where evidences are instantly created. The organizational structure, along with its context, input, goals, rules, regulations, climate, and information system, is important in the study of the effectiveness and public spending in education, research, and development, which vary from country to country (Grimshaw et al., 2004; Mandl et al., 2008). Quality data is necessary to measure the variable of effectiveness. The implementation process of any policy in an educational institution requires teacher-student interaction as it deals with the issue of education, research, and development. The issue of accountability of the administrative authority is a new phenomenon of education research and there are few pieces of research available in this field (Heck et al., 2000). In addition, there is a lack of initiatives of including innovations in the evidence-based policy-making process (O'Connor, 2022). In this paper, effectiveness refers to the effectiveness of the decision-making process relating to the issue of education, research, and development activities along with other decisions taken by the RU officials to tackle the spread of the virus infection among students during the pandemic. In evaluating the effectiveness of the decisions of the RU officials, we took many issues into consideration, including the effectiveness of online classes in relation to factors like the state of technology-driven teaching and learning, access to internet and technical facilities of the students, vaccination, scheduling and rescheduling of class and admission test, etc.

The concern of equity in public policy relates to the just distribution of goods and services. Generally, equity amongeducation institutions means equal distribution and access to subsidies for education facilities (Winkler, 1990). The trend in the number of students in the higher education sector is increasing, which is also reflected by the government’s economic and social policy. Clancy and Goastellec (2007) argued that globalization, competition in the global market, technological change, and economic priorities changed the trend of increasing number of students in the higher education sector. They identified three preconditions to frame the students’ access to higher education policy: “inherited merit, equality of access and equity in higher education, and equity defined as equality of opportunity” (p. 137).

Thus, the equity issue in the education sector brings the issue of merit-based equal access and opportunity for all the students in the higher education sector. The equity issue during the pandemic refers to higher education authorities’ ensuring of the distance teaching and learning process, tackling of the continuity of class sessions, providing of vaccines, eliminating of mental depression among the students, etc.

Figure 1. Evaluation of decision-making process at the higher education institute during pandemic

Higher education institutions create and recreate knowledge. These institutions facilitate the development of competencies and skills, foster creative thinking, and utilize and synthesize new knowledge. They help improveleadership abilities and problem-solving approaches in special areas and develop analytical ability. Thus, higher education institutions ultimately contribute to human development (Jahan, 2015; University Grants Commission of Bangladesh [UGC], 2018; Immanuel, 1996). Higher education can be instrumental in restoring the connections among multiple issues like education, knowledge, wisdom, democratic values, social transformation, etc. (Giroux, 2009). In the transition from an industrialized society to a knowledge-based society, higher education has a vital role in preparing the young generation by providing training with problem-oriented learning, which has an ultimate impact on the economy and society (UGC, 2018). Tertiary education provides an avenue for collaborative research to boost the competitiveness and creativity of the industry, which are essential for the overall development of any country (Rahman et al., 2019). The demographic dividend could bring higher economic growth by fostering digital and technological innovations (Zaman & Sarker, 2021). In the party manifesto of the present ruling party in Bangladesh, the Awami League, the digital government agenda received enormous importance as manifested in the numerous plans and projects under this agenda (Himel & Chowdhury, 2022). However, research studies argue that these innovations are more rhetoric than reality, with the quantity and quality ofdigital innovations needing further improvement as these innovations faced numerous challenges in their implementation(Chowdhury, 2018; Sappru & Sappru, 2014).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as a part of controlling virus proliferation, all types of educational institutes remained closed in Bangladesh. There are three levels in the existing education structure of Bangladesh, i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary (Ali & Subramaniam, 2010). In Bangladesh, the Ministry of Education (MoE) and the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoP&ME) supervise and administer the education system in collaboration with affiliated directorates and departments and a diverse range of self-governing entities. The University Grants Commission of Bangladesh (UGC) is responsible to supervise both the public and private universities as well as the allocation of government grants to these educational institutions. According to the 47th Annual Report 2020 of the UGC, the total number of public and private universities in Bangladesh is 157, as of 31 December 2020. Out of these, 50 are public universities and 107 are private universities (UGC, 2021). Instead of classroom-based traditional in-person learning approaches, the universities in Bangladesh started to conduct online classes to curb the spread of coronavirus while still continuing teaching and learning activities. The process, however, had to face several challenges in a developing country like Bangladesh, such as learners’ inaccessibility to online classes due to financial constraints, low internet connectivity, high internet cost, connectivity problems, etc. (Al-Amin et al., 2021; Panday, 2020).

Based on the above discussion, this article aimed to investigate the difficulties faced by both the students and the authority of tertiary-level educational institutions concerning the COVID-19 epidemic. What initiatives were taken during the lockdown and after? What is the state of the teaching-learning environment at the University of Rajshahi (RU)? What were the problems faced by the administrative authority and the students as well and why?

Methodological issues and data collection tools

Since the subject matter of the research is a contemporary phenomenon and answers “how” “what” and “why” type of questions, this study followed a case-oriented qualitative approach (Chowdhury, 2019; Yin, 2004; Bryman, 2001; Babbie, 2004). Based on both the primary and secondary sources of data, this paper analyzed the dilemmas of policy response regarding the tertiary-level educational institutions in Bangladesh. Since many public universities in Bangladesh have separate laws and regulations, the case of RU was selected for extensive analysis. RU, which has 59 departments, is one of four universities in Bangladesh where the authorities can make decisions on their own as per a 1973 ordinance. It has a total of over 38,000 students (The Daily Prothom Alo, 2022). Data for the case study has been drawn from a total of tenkey informant interviews (KII) of administrative and academic staff. Two focus group discussions (FGD)—one among the male students and another among the female students of the Department of Public Administration of RU—were conducted. The secondary sources included content analysis of newspapers, open data on the website of the university, published journal articles, etc.

This article has a total of six sections. The first section is a discussion of the background of the paper. The second segment is on the development of a theoretical framework and a discussion on the framework of the policy process model. With regard to the objective of the paper, the third section gave an overview of the existing decisions of RU officials and the state of teaching and learning with a broader perspective to understand the dilemmas specifically. The fourth section analyzed the empirical data drawn from KIIs and FGDs, and then followed by data substantiation from published articles. The discussion section provides the actual understanding of the outcome based on the policy framework. The conclusion section offers further research agenda.

Theoretical framework: An analysis of the policy process model

In the early 1970s, public policy practitioners analyzed public policy through the application of formal and mathematical methods to solve the problems of the public sector. It is a field to discuss the interrelation between the government and the beneficiary client. There are two approaches to analyze government policies. First is policy analysis, which tries to solve problems using mathematical and statistical models. The second approach is political public policy, which is concerned with the consequences or outcomes of public policies on health, social welfare, education, and the environment, other than the application of statistical methodologies. Anderson (1997) defines public policy as the "relationship of a government unit to its environment" (cited in Wilson et al., 2020, p. 125). Anderson sees public policy as a tool that governments employ to build strategies and processes for tackling social issues in a specific setting. In the context of the study of policymaking and implementation in public administration, policy denotes the guidance for action. It may take the form of a declaration of guiding principles; a declaration of definite course of action; and a program of activities (Sappru, 1994, p. 133). Policy, planning, and decision-making are three different concepts with underlying different connotations. The scope of the concept of “policy” has a wider connotation, whereas planning has a limited scope. On the other hand, the process of decision-making is concentrated on the issues that are important to achieve planned goals. Policy means a course or principle of action adopted or proposed by an organization or individual, while planning generally refers to the process of thinking about and organizing the activities necessary to attain the intended outcome. Decision-making is described as a method of choosing the best and most effective plan of action from a set of two or more options for achieving the desired result.

There are many theories and related concepts in the policy process studies—from identifying issues to implementing policies. There is no specific model applicable to all types of policy analysis. The policy analysis model of Patton and Sawicki (1986) gave us an idea about how policy analysts should follow some steps to take a policy and make a decision. The strength of this model is that it provides guidelines for dealing with a particular policy problem as well as prepares a suitable alternative solution to resolve the problem. The first step of this model includes verifying, identifying, and detailing the problem. because it seems challenging to define problems in broader areas of the public policy arena like education, health, or public welfare. Again, the statement of the problem should identify specific problems, focus on acentral issue, and include only critical factors rather than dwelling on unnecessary issues. The analyst must be efficient in preparing a detailed statement of the policy problem and estimating the time and resources for future courses of action. Effectiveness, equity, and political acceptability are three important dimensions in the second phase for establishing evaluation criteria. Identifying alternative policies, evaluating the policies, displaying and distinguishing alternative policies, and monitoring the implemented policy are several other steps that are followed by the policy analyst in the next phase. There are many studies relating to policy formulation and policy implementation processes. Considering the study objective, this paper analyzed the second step of this policy process model: the evaluation criteria of the policy decision (Figure 1).

Effectiveness, equity, and political acceptability are factors that are used in the evaluation criteria for analyzing policies to be taken to address a given problem. Effectiveness refers to the outcome of the intended objective of the policy. This paper deals with the issue of effectiveness during a crisis, where evidences are instantly created. The organizational structure, along with its context, input, goals, rules, regulations, climate, and information system, is important in the study of the effectiveness and public spending in education, research, and development, which vary from country to country (Grimshaw et al., 2004; Mandl et al., 2008). Quality data is necessary to measure the variable of effectiveness. The implementation process of any policy in an educational institution requires teacher-student interaction as it deals with the issue of education, research, and development. The issue of accountability of the administrative authority is a new phenomenon of education research and there are few pieces of research available in this field (Heck et al., 2000). In addition, there is a lack of initiatives of including innovations in the evidence-based policy-making process (O'Connor, 2022). In this paper, effectiveness refers to the effectiveness of the decision-making process relating to the issue of education, research, and development activities along with other decisions taken by the RU officials to tackle the spread of the virus infection among students during the pandemic. In evaluating the effectiveness of the decisions of the RU officials, we took many issues into consideration, including the effectiveness of online classes in relation to factors like the state of technology-driven teaching and learning, access to internet and technical facilities of the students, vaccination, scheduling and rescheduling of class and admission test, etc.

The concern of equity in public policy relates to the just distribution of goods and services. Generally, equity amongeducation institutions means equal distribution and access to subsidies for education facilities (Winkler, 1990). The trend in the number of students in the higher education sector is increasing, which is also reflected by the government’s economic and social policy. Clancy and Goastellec (2007) argued that globalization, competition in the global market, technological change, and economic priorities changed the trend of increasing number of students in the higher education sector. They identified three preconditions to frame the students’ access to higher education policy: “inherited merit, equality of access and equity in higher education, and equity defined as equality of opportunity” (p. 137).

Thus, the equity issue in the education sector brings the issue of merit-based equal access and opportunity for all the students in the higher education sector. The equity issue during the pandemic refers to higher education authorities’ ensuring of the distance teaching and learning process, tackling of the continuity of class sessions, providing of vaccines, eliminating of mental depression among the students, etc.

Figure 1. Evaluation of decision-making process at the higher education institute during pandemic

Source: Authors’ own, adapted and developed from Patton & Sawicki’s (1986) model of policy process

Political acceptability refers to the receptiveness of public policy by key actors and clients in political conditions. The reform agenda in the form of digitalization has been changing the service delivery system of Bangladesh gradually since the present government came to power in late 2008. However, researches show that if reforms are poorly understood by the implementers, they cannot facilitate ownership among policy implementers (Bush et al, 2021). In this situation, the compatibility of both the agenda for reform initiatives and implementation faces numerous challenges. In the higher educational institute during this pandemic, it was a matter of exploring how far this digitalization mandate of the ruling political party has materialized. This was important for two reasons. One reason is to assess the success of the party manifesto. The second reason is to tackle the challenge of the pandemic. Among the key actors who were involved in the decision-making process are the cabinet division, the health ministry, the education ministry, etc. The ruling political party’s role, along with its political manifesto of digitalization, is a major consideration in analyzing policy dilemmas inthe decisions of RU officials. Thus, the issues, such as the state of technology-driven teaching and learning among others,got prominent importance in the analysis of the issue of political acceptability in this paper. Other issues include the role of the telecommunication sector with regard to relating to internet coverage, subsidy for students to access to internet and other technical facilities, the role of the health ministry in the vaccination process, etc.

Decisions taken during the pandemic: Receptiveness of key actors

Since December 2019, the world has been going through a tough period as the COVID-19 pandemic hit humanity hard. The pandemic has a long-term impact that cannot be assessed at once. Education is one of the sectors where the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was evident (Raihan et al., 2021). As per the report of UNESCO (2020a), more than 60% of all students in the world were negatively impacted by the sudden closure of all educational institutions across the globe due to the coronavirus. A large number of students survived with low economic capacity. Thus, equityis about considering the students’ demands with regard to distance learning. These sudden changes like isolation or staying at home have significantly contributed to students’ anxiety and depression (Brooks et al., 2020). The World Bank (2019) revealed that the tertiary-level educational institutions in Bangladesh failed to balance the supply side of required employable graduates consistent with the demand of employers for more highly-skilled professionals for managerial and technical positions in the service and industry sectors. Thus, the rate of unemployment was significantly higher among graduates. A highly competitive job market and prolonged unemployment were making graduates frustrated more and more. The scenario was comparatively better regarding polytechnic students as their technical knowledge is a priority in the job market. Moreover, the rate of unemployment was higher among female graduates, which was three times more than males. A study conducted by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM) (Raihan et al., 2021) on the impact of the pandemic on the poverty incidence in Bangladesh showed that 42% of 5,577 households were living below the poverty line and 51.1% of them were service holders who lost their job due to the pandemic. Amidst this situation, the declining socioeconomic conditions in Bangladesh can be a factor in the mental condition of students. A large portion of students, especially in public universities, belong to middle-income and lower-income families (Raihan et al., 2021). Another study found that during the pandemic female university students were suffering more depression (i.e., moderate 24% and moderately severe 17%) and anxiety (17% moderate and 30% severe) compared to their male counterparts (20% moderate and 1% moderately severe depression while 16% moderate and 14% severe anxiety) (Rezvi et al., 2022).

The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) ordered the closure of educational institutions as an immediate response to the proliferation of coronavirus in March 2020 (Das, 2021). However, to keep in mind the issue of social distance, as per the advice of the World Health Organization (WHO) and GoB, tertiary-level education moved towards an online education strategy (Panday, 2020). Because of this outbreak, all students were compelled to return to their homes leaving university residential halls or hostels. The outbreak of the COVID-19 posed a gargantuan impact on human health. The virus has also affected teaching and learning activities around the globe. Amid the imposed lockdown, travel restrictions, and physical distancing, governments of several countries responded to the decision of closing down all kinds of educational institutions to prevent the rapid spread of the highly infectious disease. Until 25 March 2020, governments of 150 countries shut down all types of educational institutions, affecting more than 80% of the global student population (UNESCO, 2020b). In light of rising concern about the devastating consequences of COVID-19, the GoB too decided to close all types of educational establishments. The Education Minister announced the suspension of educational activities from primary to tertiary level (United News of Bangladesh, 2020). In line with the government’s decision, the University of Rajshahi suspended all its academic activities, and students were asked to vacate residential halls (The Daily Star, 2020).

Table 1. Policy responses to the pandemic by RU officials

Political acceptability refers to the receptiveness of public policy by key actors and clients in political conditions. The reform agenda in the form of digitalization has been changing the service delivery system of Bangladesh gradually since the present government came to power in late 2008. However, researches show that if reforms are poorly understood by the implementers, they cannot facilitate ownership among policy implementers (Bush et al, 2021). In this situation, the compatibility of both the agenda for reform initiatives and implementation faces numerous challenges. In the higher educational institute during this pandemic, it was a matter of exploring how far this digitalization mandate of the ruling political party has materialized. This was important for two reasons. One reason is to assess the success of the party manifesto. The second reason is to tackle the challenge of the pandemic. Among the key actors who were involved in the decision-making process are the cabinet division, the health ministry, the education ministry, etc. The ruling political party’s role, along with its political manifesto of digitalization, is a major consideration in analyzing policy dilemmas inthe decisions of RU officials. Thus, the issues, such as the state of technology-driven teaching and learning among others,got prominent importance in the analysis of the issue of political acceptability in this paper. Other issues include the role of the telecommunication sector with regard to relating to internet coverage, subsidy for students to access to internet and other technical facilities, the role of the health ministry in the vaccination process, etc.

Decisions taken during the pandemic: Receptiveness of key actors

Since December 2019, the world has been going through a tough period as the COVID-19 pandemic hit humanity hard. The pandemic has a long-term impact that cannot be assessed at once. Education is one of the sectors where the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was evident (Raihan et al., 2021). As per the report of UNESCO (2020a), more than 60% of all students in the world were negatively impacted by the sudden closure of all educational institutions across the globe due to the coronavirus. A large number of students survived with low economic capacity. Thus, equityis about considering the students’ demands with regard to distance learning. These sudden changes like isolation or staying at home have significantly contributed to students’ anxiety and depression (Brooks et al., 2020). The World Bank (2019) revealed that the tertiary-level educational institutions in Bangladesh failed to balance the supply side of required employable graduates consistent with the demand of employers for more highly-skilled professionals for managerial and technical positions in the service and industry sectors. Thus, the rate of unemployment was significantly higher among graduates. A highly competitive job market and prolonged unemployment were making graduates frustrated more and more. The scenario was comparatively better regarding polytechnic students as their technical knowledge is a priority in the job market. Moreover, the rate of unemployment was higher among female graduates, which was three times more than males. A study conducted by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM) (Raihan et al., 2021) on the impact of the pandemic on the poverty incidence in Bangladesh showed that 42% of 5,577 households were living below the poverty line and 51.1% of them were service holders who lost their job due to the pandemic. Amidst this situation, the declining socioeconomic conditions in Bangladesh can be a factor in the mental condition of students. A large portion of students, especially in public universities, belong to middle-income and lower-income families (Raihan et al., 2021). Another study found that during the pandemic female university students were suffering more depression (i.e., moderate 24% and moderately severe 17%) and anxiety (17% moderate and 30% severe) compared to their male counterparts (20% moderate and 1% moderately severe depression while 16% moderate and 14% severe anxiety) (Rezvi et al., 2022).

The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) ordered the closure of educational institutions as an immediate response to the proliferation of coronavirus in March 2020 (Das, 2021). However, to keep in mind the issue of social distance, as per the advice of the World Health Organization (WHO) and GoB, tertiary-level education moved towards an online education strategy (Panday, 2020). Because of this outbreak, all students were compelled to return to their homes leaving university residential halls or hostels. The outbreak of the COVID-19 posed a gargantuan impact on human health. The virus has also affected teaching and learning activities around the globe. Amid the imposed lockdown, travel restrictions, and physical distancing, governments of several countries responded to the decision of closing down all kinds of educational institutions to prevent the rapid spread of the highly infectious disease. Until 25 March 2020, governments of 150 countries shut down all types of educational institutions, affecting more than 80% of the global student population (UNESCO, 2020b). In light of rising concern about the devastating consequences of COVID-19, the GoB too decided to close all types of educational establishments. The Education Minister announced the suspension of educational activities from primary to tertiary level (United News of Bangladesh, 2020). In line with the government’s decision, the University of Rajshahi suspended all its academic activities, and students were asked to vacate residential halls (The Daily Star, 2020).

Table 1. Policy responses to the pandemic by RU officials

Lockdown Period |

Decisions Undertaken by Cabinet |

Decisions Undertaken by RU Officials |

2020 (total of 10 months) 17 -31 March 1 - 14 April; 15 April- 29 May; |

16 March 2020 Closure of educational institutions |

Closure of RU residential halls and departments |

30 May- 12 June; 13 June- 31 July; 1 - 31 August; 1 September- 3 October; 4 - 31 October; 1- 14 November; 1- 19 December |

On 9 July 2020, online classes started; |

|

2021 (total of 2 months) 20 December 2020- 16 January 2021; 14 February- 28 February 2021. |

On 1 March 2021, the RU officials decided to conduct the admission test on 14 June 2021; On 11 May 2021, registration began for COVID-19 vaccination for RU students. On 20 May 2021, the admission test was postponed for one month On 4 October 2021, the admission test started On 17th October 2021, the decision was taken to reopen the university's residence halls and academic activities after students have been given the first and second doses of the Covid-19 vaccine. |

|

2022 |

On 15 February 2022, RU authorities decided to resume classes from 22 February 2022 due to the Omicron wave. |

Source: Content analysis of published news (2020-2022)

During the early stages of the pandemic, all the actors engaged in the crisis management system were not aware of the unforeseen consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. The very first decision regarding the pandemic was the postponement of the Mujib Borsho celebration, the birth centennial of the Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The government closed all educational institutions on 16 March 2020. The instruction circular was issued by the cabinet division as a precautionary initiative against the proliferation of novel coronavirus (The Daily Star, 2020). By 30 April 2020, the number of coronavirus-infected persons in Bangladesh had reached 7339.[1] A full lockdown was imposed in some areas, while others had limited movement. The closure of educational institutions was extended from time to time (Table 1). During these days, the cabinet division issued instruction circulars at given time periods in 2020 and 2021.

Soon after the outbreak of the coronavirus, the Education Minister of Bangladesh Dr. Dipu Moni presided over a high-level meeting on 19 March 2020 to sort out the strategy for the continuation of tertiary-level education. Responsible officers of the Ministry of Education (MoE) as well as representatives of UGC were present at the meeting. The key takeaway of that meeting was that all the faculty members of public and private universities would be authorized to use the platform Bangladesh Research and Education Network (BdREN) for conducting online classes.[2] The UGC approached all the universities, especially public universities to conduct virtual sessions from July 2020 at the peak of the pandemic (Kamal, 2020). On 9 July 2020, the RU authorities decided to start online classes on 12 July 2020 (Kaium, 2020). On 1 March 2021, RU had planned to administer the entrance exam on 14 June 14 of the same year. Conducting the admission test was necessary because of the increasing session gap, which was causing frustration among students.

On 20 May 2021, the admission test for the 2020-21 academic year had been pushed back by a month. Later, the RU authorities chose to conduct the entrance exam on 16 August instead of 14 June. After changing the date several times due to inevitable reasons, the admission test for the academic year 2020-2021 began on 4 October 2021, at the RU campus (The Daily Star, 2021b). The Academic Council of RU decided to reopen the university's residential halls on 17 October 2021 in a meeting held on 30 September 2021. During the meeting, it was also decided to resume academic activities on 20 October 2021 (The Daily Star, 2021c). Taking at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine has been made mandatory for all students. Otherwise, nobody was supposed to be allowed to enter the dormitory and classroom. Students wererequested to complete their vaccination registration before accessing the dormitories and classrooms (Daily Bangladesh, 2021). The process of online registration for the students of RU to get vaccinated against COVID-19 started on 11 May 2021. The RU administration had asked the students to get registered by 24 May 2021 (Dhaka Tribune, 2021). By 17 October 2021, all the necessary arrangements had been set in place to provide RU students with the COVID-19 vaccine. Shaheed Sukhranjan Samaddar[1] Teacher-Student Cultural Center (TSCC) of the university was selected as the venue of the vaccination program (The Policy Times, 2021) to inoculate more students at a time as well as follow the social distancing protocol.

On 14 January 2022, a set of directives regarding health protection was issued by the RU authority to safeguard its students and staff from being infected with COVID -19. To avoid the spread of the virus, all stakeholders of RU were requested to comply with the protocol, which included getting immunized and using face masks. To make up for the academic losses, the chief decision-making authority of the university had also decided to cancel both the summer and winter vacations. Other initiatives undertaken by the RU administration were a campaign for immunization to ensure full vaccination for all the students against coronavirus, and the establishment of a COVID-19 sample collection center and a 24-bed COVID-19 isolation unit (Dhaka Tribune, 2022a).

On 15 February 2022, after the Omicron wave, the RU authority decided to resume classes of all academic sessions in person from 22 February 2022. The authority requested students to follow the health guidelines and be extra vigilant in protecting their health. Previously, the university had suspended in-person classes from 7 February to 21 February 2022 following cabinet division guidelines released on 21 January 2022 (Dhaka Tribune, 2022b).

The role of RU authority: An analysis of the effectiveness and equity issues

The analysis of the above section revealed that the decision regarding the closure of all the educational institutions wasissued by the cabinet division. The RU officials received technical and financial support from UGC to conduct online classes. Initially, these decisions received some resistance among students but after a while, they took it positively. The subsequent sections deal with the issues of effectiveness and equity issues during the pandemic:

Lack of capacity of both the teachers and students for interactive online classes

Some of the advantages of online education during COVID-19 were keeping students engaged with their academic activities, completing courses on time, and maintaining communication between students and teachers. However, the lack of digital literacy, inadequate training of teachers, incorrect adaptability to virtual classrooms, and faculty unpreparedness were impeding the effective functioning of online education (Alam, 2020; Dubey & Pandey, 2020). The capacity of the teachers to conduct online classes was one of the major concerns faced by the teaching-learning system during the pandemic at RU. The RU authorities had undertaken initiatives to address the need for training for capacity building of teachers to conduct online classes. A respondent from the Information and Technology Centre (ICT) of RU stated the following observations:

Several faculty members faced difficulties while conducting online classes because of having no training on technical issues. It would have been easily resolved by taking timely actions to provide adequate training on the same to the faculty members. The RU authorities, the ICT in particular, tried to give adequate support to them at that time. Two or three departments collectively requested me to conduct a session on how to take classes via Zoom app. We helped them.

The inadequacy of managing training needs to conduct online classes by the RU authorities was also a challenge. According to one of the respondents,

I think around 30-40% of teachers of RU did not take any online classes because they did not have that know-how. They do not know how to open an email account, they do not have accounts on Zoom app, or do not know how to use Zoom.

During the pandemic, there were several factors that affected tertiary-level students’ motivation to study like the lack of direct conversations with friends and teachers, no option to group study, and no chance to go for library work (Dutta &Smita, 2020). Multiple respondents identified the lack of teacher-student interaction as one of the major challenges in the teaching-learning process. The interaction between students and teachers was aggravated by mental health issues that were triggered by the closure of RU. The issue of adaptability of students to online class setting and the absence of capacities to participate in such classes were addressed. According to one of the respondents,

You cannot expect that face-to-face interaction in the classroom and virtual interaction will be the same. Those who are used to online communication, for example, attending or conducting virtual meetings for many years, are accustomed to it. Adapting to such a system is not easy for all. Many students cannot use the ‘raising hand’ feature on Zoom and cannot talk without fear in online classes. However, one of the major issues in the online teaching-learning system at RU is the large number of students. It is not easy to identify them while the class is going on. Rather, a limited number of students in online classes would be more convenient.

The students were demotivated to participate in online classes due to the lack of interaction, absence of informal communication, coordination among students, and a one-way class lecture delivery system. According to a participant inthe FGD session:

I do not like online classes as there is no way of informal communication and cooperation with my friends during online classes. In addition, the online class seems a one-way delivery system. The teacher is delivering his/her lectures while the students are just listening. There is hardly an interaction. The way some teachers conducted online classes; it seemed interesting to participate in the class. But in some cases, it was monotonous to join the class and I used to eat by leaving my phone in my room while the class was ongoing. Some teachers did not try to communicate with us. They just offered lectures and did not even ask us a single question. Then, I felt like there is no need to concentrate on the class. My attendance would be counted if I just kept logging in to Zoom.

However, the study has found a new dimension of learning added by virtual classrooms that seems beneficial to students. According to one of the respondents,

Despite several issues, the online class system is a blessing too. It opens a new dimension of learning. It does not take much physical or mental preparation to join an online class. Online education has taught students as well as teachers to use and learn about online platforms like Zoom as a medium for teaching-learning.

The incapacity of both the teachers and students, which was inadequately tackled by RU authorities, coupled with students’ mental health issues put hindrance to the teaching-learning process of RU.

The long school closure aggravated the digital divide

The decision of keeping the university closed had been effective in reducing the number of new cases of COVID-19 infection. But the long closure of universities adversely affected educational outcomes. The students were greatly challenged by the gap in the academic curriculum due to the school closures. Hence, online education was introduced as a possible option to recover the losses of the academic sector.

The socioeconomic situation of the students impacts the online education outcome. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) revealed that only 5.6% of Bangladeshi households owned a computer at home in 2019, while only 37.6% of households had internet connectivity at home. Based on the data of UGC, 14% t of approximately five lakh of public university students lack internet connectivity (Kamal, 2020), which posed as a challenge to ensure online education for tertiary-level students in Bangladesh.

In the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2020, about 12.7 % of low-income households had no mobile phone, which was, along with steady internet connection, the minimum requirement for a student to be able to participatein virtual sessions (Tariq & Fami, 2020 as cited in Al-Amin et al., 2021). Students from middle-income often encountered difficulties in acquiring the required devices or broadband/wi-fi connections to take part in online classes. There were also challenges regarding the disbursement of financial allocation provided by the government to assist such students. Another issue was the cost-effectiveness of the procedure for applying for a loan for the financial challenges of students during lockdowns. According to a participant of FGD,

I thought of applying for the loan but could not as I had to come to the university to apply for that loan. During that time, there were travel restrictions. Besides, I thought that the cost of coming to the university seemed more than the amount that would be provided as a loan.

Moreover, it is not clear whether the selected students for financial support have received the amount they had loaned or not. According to one of the respondents,

I heard about the loans and it was issued in my name. But I did not get any further feedback.

The absence of proper monitoring of the disbursement of loans means it is not also clear whether the objective of meeting the need of purchasing a phone or laptop for the students was met. This is noted in the following account of an interview respondent:

The UGC took many decisions on the allocation of loans to the students for buying smart devices like phones and laptops. After several negotiations with the government, UGC decided to give a maximum of 25000 BDT as loans to the students. A list of almost 4000 students of RU was sent to UGC. Probably a total of 700 students were given loans. The students were given a condition that after buying a device they must deposit the voucher into the accounts section of the university. I have no feedback on whether they deposited it or not. Did the students buy devices with the loans or spend them on other things?

Moreover, the proportion of financial support received by students at RU compared to the socioeconomic condition of students, as shown in the FGD and the study of SANEM (Raihan et al, 2021), is indicating the inadequacy of financial support to cope with the pandemic situation.

Reports revealed that the cost of online classes had put a financial burden on parents during the COVID-19 pandemic (Alamgir, 2020). The citizens of Bangladesh spend more ($0.99 per gigabyte) on buying internet data than the citizens of India and Sri Lanka (The Business Standard, 2022). However, the government decreased the cost of internet through the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) during the COVID-19 pandemic. If a student has to attend three to five classes in a week having the video camera turned on, she/he may need a minimum of five gigabytes of internet data, which would cost 1000 BDT per month. This observation regarding the financial hardship of the students is reflected in the response of one of the FGD participants:

All of us are not able to have Wi-Fi connections installed in our homes. If we stay at the university campus, there is a little bit of opportunity to browse the internet. But in case we are at our home, we have to purchase mobile data and it costs nearly 38 BDT to buy 1 GB of internet data, which is almost consumed in just an hour of online class. It was like a burden to my middle-class family to spend money to purchase internet packages daily. Facilities with internet packages were one of the crucial issues. Once the data connection is consumed, it would take one or two days of waiting for an internet promo so that it would cost less. Sometimes, I did not have money in my mobile banking account to purchase internet data and could not get the opportunity to reload my account.

During the pandemic, when people were already going through a financial crisis, online classes have put an extra financial burden on a large number of RU students.

Technological limitations

The benefits of internet connection are not equally enjoyed by the students across Bangladesh. M any remote areas still remain out of network coverage. As a result, students from rural areas faced challenges to effectively take part in online classes (Mamun, 2021). Internet speed was identified as one of the major challenges. According to one of the interview respondents:

The three main technological issues are internet speed, the digital divide, and the technical know-how of users. I put technical know-how in the last as I think most of the students can operate Zoom now. I would like to concentrate more on whether they have the capabilities to buy a smartphone or a stable internet connection. Without these two requirements, you’ll be unable to take part in the virtual classes.

The study conducted by Al-Amin et al. (2021) on the students of several Bangladeshi universities found that students living in city corporations benefited more from the virtual sessions than countryside students. Al-Amin et al. (2021) also revealed that 49% of students had encountered power outages while three-fourths (75%) had no stable internet access during online learning sessions. The challenges created by the limitation of the infrastructure of internet and electricity facilities in the countryside need to be addressed. According to one of the respondents,

There is a lack of reliable internet infrastructure in many marginalized areas in Bangladesh. As a result, many students cannot get connected to online classes. Even when I took online classes, I saw students climbing trees or by the riverside just to have stable internet access. Although by taking loans, your parents can buy you a smartphone, but you cannot still take part in online classes without strong internet networks. The RU authorities had all the required support needed to for an online teaching-learning system. We could not incorporate the students into the online teaching-learning system as they had infrastructural problems. Rural students have not only network issues but also face issues regarding their ability to take part in online classes because of electricity problems.

The FGDs and interviews revealed that slow or no connectivity issue was the reason for some students not attending classes. Despite having devices to join online classes, sometimes students were unable to join virtual classes due to slowinternet speed as an outcome of an interruptive internet network. Many of the respondents have similar experiences:

● My home is in the hill tract area. I hardly have electricity and internet network. Despite the existing obstacles, I tried to attend online classes but ended up joining only a few classes due to a lack of mobile data and buffering network speed. (Male participant A)

● There was less opportunity to take down notes during class lectures. Especially when the weather was bad, it was impossible to join the classes. (Female participant B)

● Moreover, when a student raise a hand to say something during the class, both the teacher and other students had difficulty understanding what the student was saying as audio was stuttering/ choppy due to an interruptive internet connection. (Male participant C)

Though the government has allocated some financial support to students, it failed to reach the students due to procedural shortcomings. Priyo and Hazra (2021) observed that online education could not ensure equity as there is a digital divide among the students. Based on the responses of the participants, the lack of mobile device or laptop computer and internet connectivity, poor internet network, high cost of mobile data, low literacy regarding digital technologies, and lack of required infrastructure as well as resources are contributing factors to the digital divide (Al-Amin et al., 2021).

Discussion

Monitoring the outcome of decisions implemented during the pandemic is a crucial task in the policy analysis process. The dilemmas of policy responses differ from country to country. Akanda & Ahmed (2020) found that the government of Bangladesh tackled the spread of the virus by taking stringent measures as observed in the findings of the study. Managing the spread of infection and enabling the continuing of knowledge creation at the university were two important responsibilities of the RU authorities. The initiatives that were taken by the RU authorities were commendable in terms of effectiveness. We observed that the conduct of online classes is affected by several factors such as the state of technology-driven teaching and learning, students’ access to internet and other technical facilities, vaccination, scheduling and rescheduling of class and admission tests, etc. The ineffectiveness of interaction between teacher and students was not only evident in RU, this was found in other South Asian countries too such as India, Nepal, etc. Notably, the goal of higher education is the improvement of the critical thinking of students, which became a challenge (Pokhrel & Chhetri, 2021).

Secondly, we presumed that equity ensures equal opportunity for all. Data from other South Asian countries resembled our findings in the case of RU. In particular, the issues that surfaced are the digital divide among students, lack of willingness to participate in the online platform due to technical constraints, lack of availability of devices, internet connectivity, economic constraints, less interactive classes, mental health issues among students., dependency on primary data for research while relegating the importance of secondary sources, postponing assignments and fieldwork, etc. (Al-Amin et al., 2021; Muthuprasad et al. 2021; Khati & Bhatta, 2020; Hosen et al. 2022; Methodspace, 2021).

Thirdly, we operationalized the political acceptability of the digitalization mandate during the pandemic from two perspectives. First is to address the challenge of the pandemic. In our study, the findings suggested that although the RU authorities had the discretion of taking decisions to address the challenges of the pandemic, initially, it followed the directives from the cabinet division circular. The guidelines set by the circular were necessary to control the spread ofinfections before the invention of the vaccine. However, the RU authorities gradually decided to conduct online classes. This decision was politically viable and would ensure the safety and health of both the teachers’ and students’ during the pandemic. The decisions of the cabinet division and the role of the health and education ministries illustrate the importance of decision-making during crisis. The second perspective is to assess the success of the party manifesto. The manifesto’s agenda of digitalization—the distance e-learning process and e-vaccination registration—got political acceptability from various sections of society. The case of RU is an exemplary demonstration of the coordination of different actors in managing a crisis. The university was preoccupied with technological support, which was in accordance with the agenda of digitalization of the present ruling party. The online teaching and learning process is instrumental for the students to continue with their academic activities, complete their courses on time and maintaincommunication with their fellow students and with their teachers. This led us to conclude that the implementation process of the policy decisions had clearly defined objectives and had less ambiguity among the implementers. Importantly, the immediate decision of the cabinet division to issue a circular and the compliance of all the educational institutions tothose directives were essential during the acute period of the pandemic. Political measures for policy or program outcomes that take into account the impact on power groups like relevant decision-makers, administrators, and legislators have strengthened the performance legitimacy of the government (Chowdhury & Hossain, 2022). Digitalization—the political manifesto of the present ruling party Bangladesh Awami League—appears to support the circulation of important notices, policy decisions, and announcements of deadlines for scheduling and rescheduling dates of closure of offices, educational institutions, and vaccination process, etc.

Conclusion

The evaluation criteria in the policy process model of Patton and Sawicki (1986) leads us to conclude that effectiveness, equity, and political acceptability variables are important to assess policy decisions. Considering the economic constraints, virtual learning puts undue strain on both teaching and learning (Ane & Nepa, 2021; Rahman, 2021). Dutta and Smita (2020) recommended in their study the necessity of taking all possible steps to provide training on technical capacities regarding virtual classes to all tertiary-level students to ensure the effectiveness of online education-related decisions. The digital divide, the lack of capacity of the teachers to conduct online classes, and the lack of interaction among students and between students and teachers were some of the challenges encountered by RU students. These were the outcome of the socioeconomic background of the students, technological limitations, and the high cost of devices and internet data packages, the training needs of the teachers, the long closure of schools due to the pandemic, etc. The political leadership may consider providing an interest-free loan to tertiary-level students who are in need, with the condition of repayment after a certain period or after the student gets a job. It is necessary to improve the image of the government among the citizens and to cut down the unemployment rate which is crucial for the overall advancement of the country. The implementation of the digitalization agenda in tertiary-level educational institutions can bring economic dividends by addressing the competition of the fourth industrial revolution of the world considering social and economic considerations of development. Thus, the evaluation criteria following these variables need special attention from the policymakers for ensuring an equitable and just society. The issues including socioeconomic profile and mental health situation of the students, availability of digital devices and internet connectivity, the impact of training on the learning process, and assessment of the monetary, technological, and psychological needs of the tertiary level students necessitatefurther exploration and empirical study.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the authority of RU for providing an online platform for discussion sessions on this research topic during the pandemic, our key informants (KI), and FGD participants. This article has benefited from comments from Choudhury M Zakaria on the final draft, A H M Kamrul Ahsan, three anonymous reviewers, and the editors of Asian Review of Public Administration. All errors remain the first author alone.

During the early stages of the pandemic, all the actors engaged in the crisis management system were not aware of the unforeseen consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. The very first decision regarding the pandemic was the postponement of the Mujib Borsho celebration, the birth centennial of the Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The government closed all educational institutions on 16 March 2020. The instruction circular was issued by the cabinet division as a precautionary initiative against the proliferation of novel coronavirus (The Daily Star, 2020). By 30 April 2020, the number of coronavirus-infected persons in Bangladesh had reached 7339.[1] A full lockdown was imposed in some areas, while others had limited movement. The closure of educational institutions was extended from time to time (Table 1). During these days, the cabinet division issued instruction circulars at given time periods in 2020 and 2021.

Soon after the outbreak of the coronavirus, the Education Minister of Bangladesh Dr. Dipu Moni presided over a high-level meeting on 19 March 2020 to sort out the strategy for the continuation of tertiary-level education. Responsible officers of the Ministry of Education (MoE) as well as representatives of UGC were present at the meeting. The key takeaway of that meeting was that all the faculty members of public and private universities would be authorized to use the platform Bangladesh Research and Education Network (BdREN) for conducting online classes.[2] The UGC approached all the universities, especially public universities to conduct virtual sessions from July 2020 at the peak of the pandemic (Kamal, 2020). On 9 July 2020, the RU authorities decided to start online classes on 12 July 2020 (Kaium, 2020). On 1 March 2021, RU had planned to administer the entrance exam on 14 June 14 of the same year. Conducting the admission test was necessary because of the increasing session gap, which was causing frustration among students.

On 20 May 2021, the admission test for the 2020-21 academic year had been pushed back by a month. Later, the RU authorities chose to conduct the entrance exam on 16 August instead of 14 June. After changing the date several times due to inevitable reasons, the admission test for the academic year 2020-2021 began on 4 October 2021, at the RU campus (The Daily Star, 2021b). The Academic Council of RU decided to reopen the university's residential halls on 17 October 2021 in a meeting held on 30 September 2021. During the meeting, it was also decided to resume academic activities on 20 October 2021 (The Daily Star, 2021c). Taking at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine has been made mandatory for all students. Otherwise, nobody was supposed to be allowed to enter the dormitory and classroom. Students wererequested to complete their vaccination registration before accessing the dormitories and classrooms (Daily Bangladesh, 2021). The process of online registration for the students of RU to get vaccinated against COVID-19 started on 11 May 2021. The RU administration had asked the students to get registered by 24 May 2021 (Dhaka Tribune, 2021). By 17 October 2021, all the necessary arrangements had been set in place to provide RU students with the COVID-19 vaccine. Shaheed Sukhranjan Samaddar[1] Teacher-Student Cultural Center (TSCC) of the university was selected as the venue of the vaccination program (The Policy Times, 2021) to inoculate more students at a time as well as follow the social distancing protocol.

On 14 January 2022, a set of directives regarding health protection was issued by the RU authority to safeguard its students and staff from being infected with COVID -19. To avoid the spread of the virus, all stakeholders of RU were requested to comply with the protocol, which included getting immunized and using face masks. To make up for the academic losses, the chief decision-making authority of the university had also decided to cancel both the summer and winter vacations. Other initiatives undertaken by the RU administration were a campaign for immunization to ensure full vaccination for all the students against coronavirus, and the establishment of a COVID-19 sample collection center and a 24-bed COVID-19 isolation unit (Dhaka Tribune, 2022a).

On 15 February 2022, after the Omicron wave, the RU authority decided to resume classes of all academic sessions in person from 22 February 2022. The authority requested students to follow the health guidelines and be extra vigilant in protecting their health. Previously, the university had suspended in-person classes from 7 February to 21 February 2022 following cabinet division guidelines released on 21 January 2022 (Dhaka Tribune, 2022b).

The role of RU authority: An analysis of the effectiveness and equity issues

The analysis of the above section revealed that the decision regarding the closure of all the educational institutions wasissued by the cabinet division. The RU officials received technical and financial support from UGC to conduct online classes. Initially, these decisions received some resistance among students but after a while, they took it positively. The subsequent sections deal with the issues of effectiveness and equity issues during the pandemic:

Lack of capacity of both the teachers and students for interactive online classes

Some of the advantages of online education during COVID-19 were keeping students engaged with their academic activities, completing courses on time, and maintaining communication between students and teachers. However, the lack of digital literacy, inadequate training of teachers, incorrect adaptability to virtual classrooms, and faculty unpreparedness were impeding the effective functioning of online education (Alam, 2020; Dubey & Pandey, 2020). The capacity of the teachers to conduct online classes was one of the major concerns faced by the teaching-learning system during the pandemic at RU. The RU authorities had undertaken initiatives to address the need for training for capacity building of teachers to conduct online classes. A respondent from the Information and Technology Centre (ICT) of RU stated the following observations:

Several faculty members faced difficulties while conducting online classes because of having no training on technical issues. It would have been easily resolved by taking timely actions to provide adequate training on the same to the faculty members. The RU authorities, the ICT in particular, tried to give adequate support to them at that time. Two or three departments collectively requested me to conduct a session on how to take classes via Zoom app. We helped them.

The inadequacy of managing training needs to conduct online classes by the RU authorities was also a challenge. According to one of the respondents,

I think around 30-40% of teachers of RU did not take any online classes because they did not have that know-how. They do not know how to open an email account, they do not have accounts on Zoom app, or do not know how to use Zoom.

During the pandemic, there were several factors that affected tertiary-level students’ motivation to study like the lack of direct conversations with friends and teachers, no option to group study, and no chance to go for library work (Dutta &Smita, 2020). Multiple respondents identified the lack of teacher-student interaction as one of the major challenges in the teaching-learning process. The interaction between students and teachers was aggravated by mental health issues that were triggered by the closure of RU. The issue of adaptability of students to online class setting and the absence of capacities to participate in such classes were addressed. According to one of the respondents,

You cannot expect that face-to-face interaction in the classroom and virtual interaction will be the same. Those who are used to online communication, for example, attending or conducting virtual meetings for many years, are accustomed to it. Adapting to such a system is not easy for all. Many students cannot use the ‘raising hand’ feature on Zoom and cannot talk without fear in online classes. However, one of the major issues in the online teaching-learning system at RU is the large number of students. It is not easy to identify them while the class is going on. Rather, a limited number of students in online classes would be more convenient.

The students were demotivated to participate in online classes due to the lack of interaction, absence of informal communication, coordination among students, and a one-way class lecture delivery system. According to a participant inthe FGD session:

I do not like online classes as there is no way of informal communication and cooperation with my friends during online classes. In addition, the online class seems a one-way delivery system. The teacher is delivering his/her lectures while the students are just listening. There is hardly an interaction. The way some teachers conducted online classes; it seemed interesting to participate in the class. But in some cases, it was monotonous to join the class and I used to eat by leaving my phone in my room while the class was ongoing. Some teachers did not try to communicate with us. They just offered lectures and did not even ask us a single question. Then, I felt like there is no need to concentrate on the class. My attendance would be counted if I just kept logging in to Zoom.

However, the study has found a new dimension of learning added by virtual classrooms that seems beneficial to students. According to one of the respondents,

Despite several issues, the online class system is a blessing too. It opens a new dimension of learning. It does not take much physical or mental preparation to join an online class. Online education has taught students as well as teachers to use and learn about online platforms like Zoom as a medium for teaching-learning.

The incapacity of both the teachers and students, which was inadequately tackled by RU authorities, coupled with students’ mental health issues put hindrance to the teaching-learning process of RU.

The long school closure aggravated the digital divide

The decision of keeping the university closed had been effective in reducing the number of new cases of COVID-19 infection. But the long closure of universities adversely affected educational outcomes. The students were greatly challenged by the gap in the academic curriculum due to the school closures. Hence, online education was introduced as a possible option to recover the losses of the academic sector.

The socioeconomic situation of the students impacts the online education outcome. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) revealed that only 5.6% of Bangladeshi households owned a computer at home in 2019, while only 37.6% of households had internet connectivity at home. Based on the data of UGC, 14% t of approximately five lakh of public university students lack internet connectivity (Kamal, 2020), which posed as a challenge to ensure online education for tertiary-level students in Bangladesh.

In the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2020, about 12.7 % of low-income households had no mobile phone, which was, along with steady internet connection, the minimum requirement for a student to be able to participatein virtual sessions (Tariq & Fami, 2020 as cited in Al-Amin et al., 2021). Students from middle-income often encountered difficulties in acquiring the required devices or broadband/wi-fi connections to take part in online classes. There were also challenges regarding the disbursement of financial allocation provided by the government to assist such students. Another issue was the cost-effectiveness of the procedure for applying for a loan for the financial challenges of students during lockdowns. According to a participant of FGD,

I thought of applying for the loan but could not as I had to come to the university to apply for that loan. During that time, there were travel restrictions. Besides, I thought that the cost of coming to the university seemed more than the amount that would be provided as a loan.

Moreover, it is not clear whether the selected students for financial support have received the amount they had loaned or not. According to one of the respondents,

I heard about the loans and it was issued in my name. But I did not get any further feedback.

The absence of proper monitoring of the disbursement of loans means it is not also clear whether the objective of meeting the need of purchasing a phone or laptop for the students was met. This is noted in the following account of an interview respondent: