Asian Review for Public Administration (ARPA)

Open Access | Research Article | First published online December 20, 2023

Vol. 31, Nos. 1&2 (January 2020-December 2023)

Policy Responses to COVID-19 within the Context of SDGs: Experience from Local Governments in Vietnam

Trinh Hoang Hong Hue

Trinh Hoang Hong Hue

"Cite article"Hue, T. H. (2020-2023). Policy Responses to COVID-19 within the Context of SDGs: Experience from Local Governments in Vietnam. Asian Review for Public Administration, Vol. 31, Nos. 1&2, 47-67. |

| ||

Abstract: Good health and well-being are the essential goals to achieve sustainable development. However, having seriously hit all corners of the world since January 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has become one of the fiercest health crises in human history. It challenges governments to have prompt and accurate control actions. Although a developing country with limited resources and low technological capacities, Vietnam has succeeded in controlling the outbreak with rapid and drastic measures, especially in policy responses of the central government to COVID-19 from the early days. Simultaneously, most local governments in Vietnam also had valuable tools to mitigate this pandemic's adverse impacts in each province's unique context. This study selects three centrally controlled municipalities of Vietnam, including Ha Noi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang, as case studies to analyze their diverse policy responses to COVID-19. We analyze data on cases of infection, death, and recovery from coronavirus (COVID-19) in Vietnam by province from the Open Development Mekong website. Additionally, regarding country-level and municipal-level responses, we review relevant documents issued on the online database “Vietnam Laws Repository ”and other relevant official websites. This study aims to give insights into the municipal government's progress in policy responses in Vietnam during three waves of the outbreak, including the first wave (March – April 2020), the second wave (July – September 2020), and the third wave (January – March 2021). Based on critical elements for localizing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the local government in the future: multilevel governance, city preparedness, integrated planning, and strategy for implementation, we draw lessons from the COVID-19 responses of three cities in Vietnam, a developing country. To prepare for similar future outbreaks to fulfill SDGs, local governments may comply strictly with national guidelines and policies, public information, healthcare, adaptive behavior changes to mobility restriction, community mitigation measures, social security, and local governance.

Keywords: policy response, local government, Vietnam, COVID-19, SDGs

Keywords: policy response, local government, Vietnam, COVID-19, SDGs

Introduction

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an urgent call for action by all countries worldwide, but we must turn global goals into local action to succeed. SDGs can be localized at the grassroots or local government levels, at the forefront of the problem. We focus on local governments, specifically big cities, which are one of the critical instruments for realizing the targets. According to SDGs, good health and well-being are essential to sustainable development. Havingseriously hit all corners of the world since December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has become one of the fiercest health crises in human history. It also raises questions about the government's policy responses in the uncertainty. Countries worldwide have implemented a series of strategies to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and control the economic consequences. However, some regions or local areas are more seriously impacted since the COVID-19 pandemic has a robust territorial dimension (European Union, 2020; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2020). Therefore, local governments play an essential role in coordinating pandemic response policy, such as implementing day-to-day containment measures, ensuring health care and social services, and advancing economic development and public investment (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),2020).

Furthermore, local governance will play an essential role in the COVID-19 response. Because local governments are more closely connected to the public and can better navigate context-specific local conditions (Agrawal, 2007; Manor, 1999; Singh & Sharma, 2007). Additionally, local authorities are embedded within the societies they serve and are likely to be more responsive to the public’s urgent needs (Dutta & Fisher, 2021). Hence, local government is often perceived as more legitimate than other external actors for conducting state regulatory functions (Dutta & Fisher, 2021).

Many studies examine the central government responses to the pandemic on policy effectiveness and success within the policy sciences and public management in the case of Vietnam (Hartley et al., 2021; Hoang Viet Lam, 2021; Le et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2020;). However, although local governments expanded and established new programs and responsibilities to address the COVID 19 emergency directly, all the previously mentioned studies have less discussion about local government responses. Primarily, little is known about the collaborative actions by local governments in Vietnam amidst the COVID-19 pandemic based on efforts to maintain SDGs implementation. Hence, there is a need to shed light on the COVID-19 responses of local governments in Vietnam within the context of SDGs with good and best practices.

In the context of Vietnam, a series of policy responses have been implemented to address the COVID-19 pandemic from the central government to the local governments since late January 2020. The central government has implemented increasingly stringent lockdown measures, including closures of schools and non-essential businesses, domestic and international travel restrictions, and other social distancing measures. However, the local governments have empowered autonomy in implementing these measures due to different situations. Hence, the measures also vary by province. Vietnam has sixty-three provinces and municipalities with the same administrative level. Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang are typical representatives of three regions of Vietnam, including the North, the Central, and the South, respectively. Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, is the commercial, cultural, educational, and political center of north Vietnam. Meanwhile, Da Nang is the commercial and educational center and also the largest city in central Vietnam; and Ho Chi Minh City is the most dynamic and creative economic, financial, and technical center in south Vietnam. Over 16 months, from January 2020 to April 2021, COVID-19 has spread nationwide and mainly to these three cities at various levels. However, these local governments have effectively controlled the outbreak and continued their socioeconomic development process.

This study offers critical insight into the practice of SDGs adoption to face crises, such as COVID-19, within the local context in developing countries like Vietnam. We provide an overview of SDGs implementation in three centrally-controlled municipalities of Vietnam, including Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang. These case studies comprehensively assess how SDG targets are localized amid COVID-19 using multilevel governance (MLG) framework. We depict each local government affected by COVID-19 and analyze their diverse policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic during the initial stages of the worldwide outbreak (roughly between January 2020 and March 2021). This paper aims to answer the question: how have three cities with a total of 16 million in population managed to prevent and control a more significant outbreak in the initial COVID-19 states? Therefore, the motivation behind this paper is that there are lessons to take from early-stage crisis response, not only about public health but also about local governance. Based on critical elements for localizing SDGs in the local government—multilevel governance, city preparedness, integrated planning, and strategy for implementation—we draw lessons from COVID-19 responses from the local governments in Vietnam, a developing country. They may be a relative success in COVID-19 containment and mitigationthat help the local government of other countries to prepare for similar future outbreaks to fulfill SDGs.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Sustainable Development Goals and Local Government

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established by the United Nations (UN) in 2015, are a framework of universal goals and action targets to make the world a better and more sustainable place. The SDGs include seventeen objectives and over a hundred targets, recognizing that progress must balance social, economic, and environmental sustainability. These include poverty reduction, hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, climate change, the environment, and more (UN, 2015). Multiple parties, including UN agencies, businesses, non-governmental organizations, and national governments, must collaborate to fulfill the mandate in global cooperation due to its complexity (Florini & Pauli, 2018). With the phrase "leave no one behind," the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to reach out to every individual in a global society, resulting in various nation-states signing an agreement for global goals and putting them into action.

Remarkably, at the forefront of the delivery stage, well-defined tools with a transparent communication channel from the UN and national governments to local governments is needed (Slack, 2015). It will also offer a platform for international and local non-governmental organizations working on specific agendas. However, although a comprehensive target and activities are accessible, each goal's realization and localization are lacking (Horn & Grugel, 2018). As a result, achieving the SDGs would require collaboration among national and local governments.

The inclusion of Goal 11 to "Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable" is a result of local governments, their associations, and the urban community's arduous efforts (United City and Local Government-UCLG, 2015). SDG 11 represents a significant advance in recognizing urbanization's transformative power for development and the city leaders' role in driving global change from the ground up. However, the role of local governments in achieving the agenda goes well beyond Goal 11. SDGs have targets that are explicitly or implicitly associated with the daily activities of local and regional governments. Local governments should not be mere executors of the plan. Instead, local governments should be policymakers, change agents, and the level of government best positioned to connect global goals with local communities.

Local Governments Within the Context of Multilevel Governance

The multilevel governance (MLG) framework is a beginning point for comprehending how central governments and other public and private players collaborate to develop and implement policies at the international, national, and local levels (Hooghe & Marks, 2003). This framework has been developed and utilized to evaluate the success of cooperative frameworks in nations and urban and rural areas (OECD, 2010).

National and municipal governments cannot successfully respond to health crises like COVID-19 on their own; hence, a framework for comprehending the interconnections between levels of government and other stakeholders such as businesses and NGOs is needed. The multilevel governance approach looks at how national, regional, and local policies interact to combat the pandemic crisis. Vertical governance between levels of government and horizontal governance across sectors at the same level of government, such as involvement with non-governmental actors and governance within and between cities or territories, are all identified in such a framework (OECD, 2010). Using the framework, we plan to study the outstanding practice in the realm of local governments within the context of multilevel governance and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The MLG framework examines how multilevel government affects public administration, focusing on how the transition from government to governance has altered the interactions between networks and bureaucracy, particularly in local government (Agranoff, 2018). Hence, local governments are increasingly engaging in numerous worldwide, regional, andlocal connections, with nongovernmental organizations, and through external nongovernmental services, country actors serve their communities in several ways. Furthermore, MLG is conceived from the bottom up, from the perspective of local governments, and is grounded on their operational methods and daily organizational issues (Adam & Caponio, 2018).

National and local governments have been at the forefront of efforts to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus and mitigate the outbreak's effects on the community. Each level of government plays an essential role in the efficient implementation process, and they may not achieve the potential efficiency without acting collaboratively on the pandemic responses. National governments are uniquely positioned to determine priorities, formulate and coordinate plans, and organize considerable resource mobilization efforts (Faberi, 2018). In the absence of direct and effective engagement with local communities, however, they are frequently compelled to transfer significant portions of efficiency measures to lower levels of government. Utilizing their comprehensive understanding of the requirements and issues of the territory they administer, local authorities frequently serve as implementation agents. In addition, local governments depend on the national level in terms of cooperation with high-level strategies, the legislative framework, and the availability of financing. Therefore, many countries have coordinated responses to the COVID-19 crisis by organizing, coordinating, and delivering services in towns, cities, and provinces.

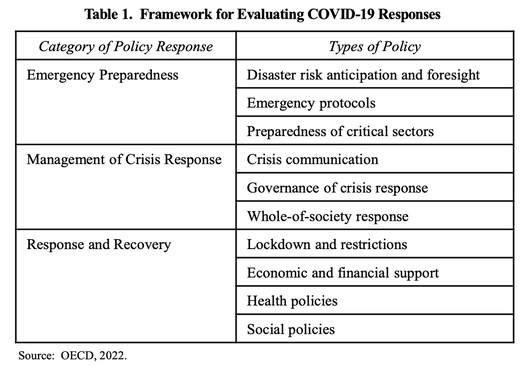

Evaluations of COVID-19's Responses: Setting the Stage

According to the OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks (OECD, 2014), governments should develop strategies and policies for each risk management cycle phase to increase their risk resilience. It has been an unprecedented challenge for most governments to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic – both in scale and in the depth of impact on health, economy, and citizens' well-being. Nevertheless, a significant amount of human, financial, and technical resources were immediately mobilized by governments to deal with the crisis and minimize its effects. Evaluations must therefore draw lessons on the relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of policies implemented at each point of this risk management cycle to understand what was done effectively – or ineffectively – in preparation for and response to the COVID-19 pandemic. When managing the epidemic, governments must assess the effectiveness of three policy measures to understand better what has and has not worked. The significant phases of the risk management cycle include pandemic preparedness, crisis management, and reaction and recovery.

For governments, the ability to predict a pandemic and prepare for a global public health disaster by having the appropriate knowledge and capacities is known as "pandemic preparedness" (OECD, 2015). Governments that understand the dangers and risks, and increase their capacity for risk foresight and analysis, may better target their prevention policymaking and mitigation programs to lessen their vulnerability (OECD, 2015). Additionally, standard operating procedures and pre-defined plans for coping with pandemics should be established through risk management processes (OECD, 2015). Notably, the pharmaceutical and healthcare industries are critical in strengthening countries' ability to combat pandemics.

Crisis management, the policies and actions governments implement to deal with the crisis once it manifests, is the next significant step of the risk cycle from which evaluations may take lessons. This includes responding quickly and effectively in the right way at the right time across government agencies (OECD, 2015). Since most of the crisis management actions are overseen and controlled at lower levels of government, coordination is essential (OECD, 2015). In addition, large-scale crises can significantly impact the public's trust in government, making it necessary to communicate clearly with the public and be transparent in decision-making during the crisis management process (OECD, 2015).

It is also important to note that response and recovery measures focus on protecting residents and companies from both the pandemic and the economic crisis. Various strategies include lockdown and restriction policies, economic and financial support for households, businesses, and markets, health measures aimed at protecting and treating the population, and social policies designed to protect the most vulnerable from the economic downturn.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an urgent call for action by all countries worldwide, but we must turn global goals into local action to succeed. SDGs can be localized at the grassroots or local government levels, at the forefront of the problem. We focus on local governments, specifically big cities, which are one of the critical instruments for realizing the targets. According to SDGs, good health and well-being are essential to sustainable development. Havingseriously hit all corners of the world since December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has become one of the fiercest health crises in human history. It also raises questions about the government's policy responses in the uncertainty. Countries worldwide have implemented a series of strategies to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and control the economic consequences. However, some regions or local areas are more seriously impacted since the COVID-19 pandemic has a robust territorial dimension (European Union, 2020; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2020). Therefore, local governments play an essential role in coordinating pandemic response policy, such as implementing day-to-day containment measures, ensuring health care and social services, and advancing economic development and public investment (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),2020).

Furthermore, local governance will play an essential role in the COVID-19 response. Because local governments are more closely connected to the public and can better navigate context-specific local conditions (Agrawal, 2007; Manor, 1999; Singh & Sharma, 2007). Additionally, local authorities are embedded within the societies they serve and are likely to be more responsive to the public’s urgent needs (Dutta & Fisher, 2021). Hence, local government is often perceived as more legitimate than other external actors for conducting state regulatory functions (Dutta & Fisher, 2021).

Many studies examine the central government responses to the pandemic on policy effectiveness and success within the policy sciences and public management in the case of Vietnam (Hartley et al., 2021; Hoang Viet Lam, 2021; Le et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2020;). However, although local governments expanded and established new programs and responsibilities to address the COVID 19 emergency directly, all the previously mentioned studies have less discussion about local government responses. Primarily, little is known about the collaborative actions by local governments in Vietnam amidst the COVID-19 pandemic based on efforts to maintain SDGs implementation. Hence, there is a need to shed light on the COVID-19 responses of local governments in Vietnam within the context of SDGs with good and best practices.

In the context of Vietnam, a series of policy responses have been implemented to address the COVID-19 pandemic from the central government to the local governments since late January 2020. The central government has implemented increasingly stringent lockdown measures, including closures of schools and non-essential businesses, domestic and international travel restrictions, and other social distancing measures. However, the local governments have empowered autonomy in implementing these measures due to different situations. Hence, the measures also vary by province. Vietnam has sixty-three provinces and municipalities with the same administrative level. Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang are typical representatives of three regions of Vietnam, including the North, the Central, and the South, respectively. Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, is the commercial, cultural, educational, and political center of north Vietnam. Meanwhile, Da Nang is the commercial and educational center and also the largest city in central Vietnam; and Ho Chi Minh City is the most dynamic and creative economic, financial, and technical center in south Vietnam. Over 16 months, from January 2020 to April 2021, COVID-19 has spread nationwide and mainly to these three cities at various levels. However, these local governments have effectively controlled the outbreak and continued their socioeconomic development process.

This study offers critical insight into the practice of SDGs adoption to face crises, such as COVID-19, within the local context in developing countries like Vietnam. We provide an overview of SDGs implementation in three centrally-controlled municipalities of Vietnam, including Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang. These case studies comprehensively assess how SDG targets are localized amid COVID-19 using multilevel governance (MLG) framework. We depict each local government affected by COVID-19 and analyze their diverse policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic during the initial stages of the worldwide outbreak (roughly between January 2020 and March 2021). This paper aims to answer the question: how have three cities with a total of 16 million in population managed to prevent and control a more significant outbreak in the initial COVID-19 states? Therefore, the motivation behind this paper is that there are lessons to take from early-stage crisis response, not only about public health but also about local governance. Based on critical elements for localizing SDGs in the local government—multilevel governance, city preparedness, integrated planning, and strategy for implementation—we draw lessons from COVID-19 responses from the local governments in Vietnam, a developing country. They may be a relative success in COVID-19 containment and mitigationthat help the local government of other countries to prepare for similar future outbreaks to fulfill SDGs.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Sustainable Development Goals and Local Government

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established by the United Nations (UN) in 2015, are a framework of universal goals and action targets to make the world a better and more sustainable place. The SDGs include seventeen objectives and over a hundred targets, recognizing that progress must balance social, economic, and environmental sustainability. These include poverty reduction, hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, climate change, the environment, and more (UN, 2015). Multiple parties, including UN agencies, businesses, non-governmental organizations, and national governments, must collaborate to fulfill the mandate in global cooperation due to its complexity (Florini & Pauli, 2018). With the phrase "leave no one behind," the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to reach out to every individual in a global society, resulting in various nation-states signing an agreement for global goals and putting them into action.

Remarkably, at the forefront of the delivery stage, well-defined tools with a transparent communication channel from the UN and national governments to local governments is needed (Slack, 2015). It will also offer a platform for international and local non-governmental organizations working on specific agendas. However, although a comprehensive target and activities are accessible, each goal's realization and localization are lacking (Horn & Grugel, 2018). As a result, achieving the SDGs would require collaboration among national and local governments.

The inclusion of Goal 11 to "Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable" is a result of local governments, their associations, and the urban community's arduous efforts (United City and Local Government-UCLG, 2015). SDG 11 represents a significant advance in recognizing urbanization's transformative power for development and the city leaders' role in driving global change from the ground up. However, the role of local governments in achieving the agenda goes well beyond Goal 11. SDGs have targets that are explicitly or implicitly associated with the daily activities of local and regional governments. Local governments should not be mere executors of the plan. Instead, local governments should be policymakers, change agents, and the level of government best positioned to connect global goals with local communities.

Local Governments Within the Context of Multilevel Governance

The multilevel governance (MLG) framework is a beginning point for comprehending how central governments and other public and private players collaborate to develop and implement policies at the international, national, and local levels (Hooghe & Marks, 2003). This framework has been developed and utilized to evaluate the success of cooperative frameworks in nations and urban and rural areas (OECD, 2010).

National and municipal governments cannot successfully respond to health crises like COVID-19 on their own; hence, a framework for comprehending the interconnections between levels of government and other stakeholders such as businesses and NGOs is needed. The multilevel governance approach looks at how national, regional, and local policies interact to combat the pandemic crisis. Vertical governance between levels of government and horizontal governance across sectors at the same level of government, such as involvement with non-governmental actors and governance within and between cities or territories, are all identified in such a framework (OECD, 2010). Using the framework, we plan to study the outstanding practice in the realm of local governments within the context of multilevel governance and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The MLG framework examines how multilevel government affects public administration, focusing on how the transition from government to governance has altered the interactions between networks and bureaucracy, particularly in local government (Agranoff, 2018). Hence, local governments are increasingly engaging in numerous worldwide, regional, andlocal connections, with nongovernmental organizations, and through external nongovernmental services, country actors serve their communities in several ways. Furthermore, MLG is conceived from the bottom up, from the perspective of local governments, and is grounded on their operational methods and daily organizational issues (Adam & Caponio, 2018).

National and local governments have been at the forefront of efforts to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus and mitigate the outbreak's effects on the community. Each level of government plays an essential role in the efficient implementation process, and they may not achieve the potential efficiency without acting collaboratively on the pandemic responses. National governments are uniquely positioned to determine priorities, formulate and coordinate plans, and organize considerable resource mobilization efforts (Faberi, 2018). In the absence of direct and effective engagement with local communities, however, they are frequently compelled to transfer significant portions of efficiency measures to lower levels of government. Utilizing their comprehensive understanding of the requirements and issues of the territory they administer, local authorities frequently serve as implementation agents. In addition, local governments depend on the national level in terms of cooperation with high-level strategies, the legislative framework, and the availability of financing. Therefore, many countries have coordinated responses to the COVID-19 crisis by organizing, coordinating, and delivering services in towns, cities, and provinces.

Evaluations of COVID-19's Responses: Setting the Stage

According to the OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks (OECD, 2014), governments should develop strategies and policies for each risk management cycle phase to increase their risk resilience. It has been an unprecedented challenge for most governments to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic – both in scale and in the depth of impact on health, economy, and citizens' well-being. Nevertheless, a significant amount of human, financial, and technical resources were immediately mobilized by governments to deal with the crisis and minimize its effects. Evaluations must therefore draw lessons on the relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of policies implemented at each point of this risk management cycle to understand what was done effectively – or ineffectively – in preparation for and response to the COVID-19 pandemic. When managing the epidemic, governments must assess the effectiveness of three policy measures to understand better what has and has not worked. The significant phases of the risk management cycle include pandemic preparedness, crisis management, and reaction and recovery.

For governments, the ability to predict a pandemic and prepare for a global public health disaster by having the appropriate knowledge and capacities is known as "pandemic preparedness" (OECD, 2015). Governments that understand the dangers and risks, and increase their capacity for risk foresight and analysis, may better target their prevention policymaking and mitigation programs to lessen their vulnerability (OECD, 2015). Additionally, standard operating procedures and pre-defined plans for coping with pandemics should be established through risk management processes (OECD, 2015). Notably, the pharmaceutical and healthcare industries are critical in strengthening countries' ability to combat pandemics.

Crisis management, the policies and actions governments implement to deal with the crisis once it manifests, is the next significant step of the risk cycle from which evaluations may take lessons. This includes responding quickly and effectively in the right way at the right time across government agencies (OECD, 2015). Since most of the crisis management actions are overseen and controlled at lower levels of government, coordination is essential (OECD, 2015). In addition, large-scale crises can significantly impact the public's trust in government, making it necessary to communicate clearly with the public and be transparent in decision-making during the crisis management process (OECD, 2015).

It is also important to note that response and recovery measures focus on protecting residents and companies from both the pandemic and the economic crisis. Various strategies include lockdown and restriction policies, economic and financial support for households, businesses, and markets, health measures aimed at protecting and treating the population, and social policies designed to protect the most vulnerable from the economic downturn.

Overview of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Vietnam

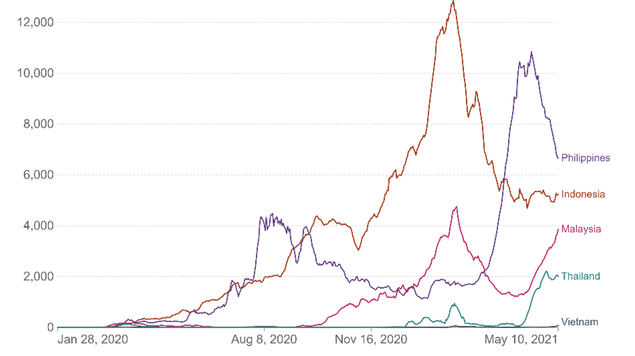

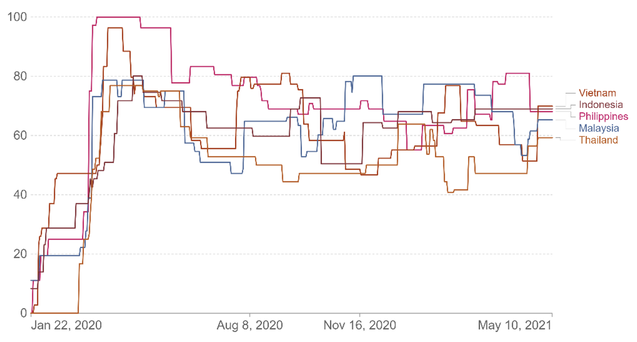

The COVID-19 pandemic originated in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China, on December 31, 2019, and spread to 211 countries. It was declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization. In early May 2021, the total number of confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19 globally was 152,534,452 and 3,198,528, respectively (WHO, 2021). COVID-19 has spread across countries with high case-facility rates that seriously disrupt human lives and economic activities worldwide. Until 10 May 2021, the number of infected cases in Southeast Asia countries has experienced a significant rise, notably in countries like Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, as shown in Figure 1 (Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2021). However, these countries have made efforts to implement timely policies to control the spread of the virus through testing and treating patients, tracing contacts, limiting travel, quarantining citizens, and so forth. Based on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (Blavatnik School of Government, 2020), the stringency index was calculated. The stringency index ranged from 0 to 100, in which the higher the score, the stricter the government policies. According to the data updated as of 10 May 2020, fluctuations of stringency indices of each Southeast Asian country (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam) by increasing confirmed cases were used to compare policy responses among these nations (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Daily New Confirmed COVID-19 Cases per Million People in Five ASEAN Countries from 28 January 2020 to 10 May 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic originated in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China, on December 31, 2019, and spread to 211 countries. It was declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization. In early May 2021, the total number of confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19 globally was 152,534,452 and 3,198,528, respectively (WHO, 2021). COVID-19 has spread across countries with high case-facility rates that seriously disrupt human lives and economic activities worldwide. Until 10 May 2021, the number of infected cases in Southeast Asia countries has experienced a significant rise, notably in countries like Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, as shown in Figure 1 (Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2021). However, these countries have made efforts to implement timely policies to control the spread of the virus through testing and treating patients, tracing contacts, limiting travel, quarantining citizens, and so forth. Based on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (Blavatnik School of Government, 2020), the stringency index was calculated. The stringency index ranged from 0 to 100, in which the higher the score, the stricter the government policies. According to the data updated as of 10 May 2020, fluctuations of stringency indices of each Southeast Asian country (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam) by increasing confirmed cases were used to compare policy responses among these nations (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Daily New Confirmed COVID-19 Cases per Million People in Five ASEAN Countries from 28 January 2020 to 10 May 2021

Source. Johns Hopkins University (2021)

Figure 2. COVID-19: Stringency Index of Five ASEAN Countries from 22 January 2020 to 10 May 2021

Figure 2. COVID-19: Stringency Index of Five ASEAN Countries from 22 January 2020 to 10 May 2021

Source. Blavatnik School of Government (2021)

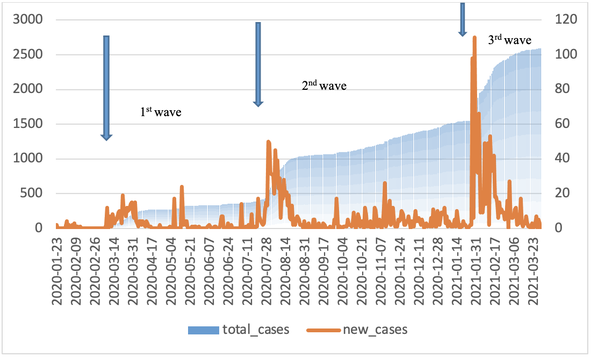

Vietnam was also unable to avoid the impacts of the spread of the virus because of the geographical proximity and the vigorous activities of traveling and trade between Vietnam and China. Therefore, we can briefly divide the development of the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnam into three waves from January 2020 to March 2021 (Figure 3). The first wave lasted from January to April 2020. The original virus strain related to Wuhan, China, was registered on 23 January 2020 in Ho Chi Minh City, and the 17th case was registered on 6 March 2020 in Hanoi. At this point, community cases with more than 53,000 people are thought to have been at risk ò exposure. Although the number of people who were infected or suspected to be infected increased sharply, no one died. The second wave started on 28 July 2020 until 30 September 2020, with the 416th case registered in Da Nang City, marking the end of more than three months without new COVID-19 cases from the local transmission. On 31 July 2020, Vietnam confirmed 82 new cases, including 45 cases in Da Nang, 20 cases in Hanoi, eight cases in Quang Nam Province, six cases in Ba Ria-Vung Tau Province, and three cases in Ho Chi Minh City. In this wave, Vietnam recorded the first deaths caused by COVID-19, which included patients with underlying severe diseases in the Da Nang Hospital cluster. The third wave of COVID-19 infections in Vietnam began from January to March 2021 in Hai Duong province with U.K. variants, then impressively spread to Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Although the number of infected people in this wave of cases is quite large, there are no severe cases and no deaths because most patients are young people.

Figure 3. Total Number of Cases and Daily New Cases of COVID-19 in Vietnam from January 2020 to March 2021

Vietnam was also unable to avoid the impacts of the spread of the virus because of the geographical proximity and the vigorous activities of traveling and trade between Vietnam and China. Therefore, we can briefly divide the development of the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnam into three waves from January 2020 to March 2021 (Figure 3). The first wave lasted from January to April 2020. The original virus strain related to Wuhan, China, was registered on 23 January 2020 in Ho Chi Minh City, and the 17th case was registered on 6 March 2020 in Hanoi. At this point, community cases with more than 53,000 people are thought to have been at risk ò exposure. Although the number of people who were infected or suspected to be infected increased sharply, no one died. The second wave started on 28 July 2020 until 30 September 2020, with the 416th case registered in Da Nang City, marking the end of more than three months without new COVID-19 cases from the local transmission. On 31 July 2020, Vietnam confirmed 82 new cases, including 45 cases in Da Nang, 20 cases in Hanoi, eight cases in Quang Nam Province, six cases in Ba Ria-Vung Tau Province, and three cases in Ho Chi Minh City. In this wave, Vietnam recorded the first deaths caused by COVID-19, which included patients with underlying severe diseases in the Da Nang Hospital cluster. The third wave of COVID-19 infections in Vietnam began from January to March 2021 in Hai Duong province with U.K. variants, then impressively spread to Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Although the number of infected people in this wave of cases is quite large, there are no severe cases and no deaths because most patients are young people.

Figure 3. Total Number of Cases and Daily New Cases of COVID-19 in Vietnam from January 2020 to March 2021

Source. Mathieu et al. (2021)

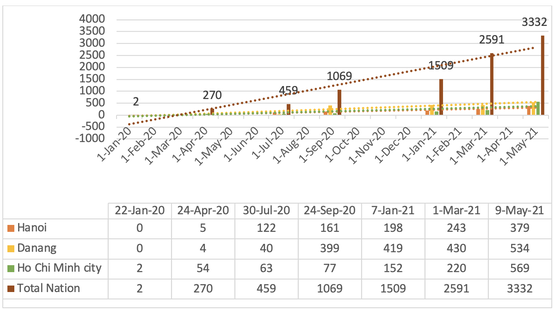

To fully understand the development of the three infection waves in Vietnam at the local level, it is necessary to analyze the evolution of COVID-19 in the provinces and cities with the most significant number of community infections in Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, and Hanoi from January 2020 to the early May 2021 (Figure 4). Three waves of COVID-19 have spread nationwide and mainly to the three cities at various levels. The first and third waves significantly affected Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, while the second wave severely affected Da Nang City. First, as the largest city in Vietnam, with a population of more than nine million, Ho Chi Minh City plays an essential role in Vietnam's economic, financial, and technical development. The city was the first to discover the first cases of COVID-19 in January 2020, which then spread to other localities. Meanwhile, Da Nang is the commercial and educational center and the largest city in central Vietnam, with a population of 1,064,100. This city entered the second wave of infection with an unknown source of infection on 28 July 2020; the first death was also recorded on 31 July 2020.

As the capital of Vietnam, Hanoi focuses on commercial, cultural, educational, and political development. Hanoi also has been affected by COVID-19 with the 17th case in Vietnam in March 2020. However, in line with the central government’s responses, these local governments effectively controlled the number of infected community cases and continued their socioeconomic development.

Figure 4. Total number of cases of COVID-19 in Hanoi, Da Nang, Ho Chi Minh City, and Vietnam from 22 January 2020 to 9 May 2021

To fully understand the development of the three infection waves in Vietnam at the local level, it is necessary to analyze the evolution of COVID-19 in the provinces and cities with the most significant number of community infections in Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, and Hanoi from January 2020 to the early May 2021 (Figure 4). Three waves of COVID-19 have spread nationwide and mainly to the three cities at various levels. The first and third waves significantly affected Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, while the second wave severely affected Da Nang City. First, as the largest city in Vietnam, with a population of more than nine million, Ho Chi Minh City plays an essential role in Vietnam's economic, financial, and technical development. The city was the first to discover the first cases of COVID-19 in January 2020, which then spread to other localities. Meanwhile, Da Nang is the commercial and educational center and the largest city in central Vietnam, with a population of 1,064,100. This city entered the second wave of infection with an unknown source of infection on 28 July 2020; the first death was also recorded on 31 July 2020.

As the capital of Vietnam, Hanoi focuses on commercial, cultural, educational, and political development. Hanoi also has been affected by COVID-19 with the 17th case in Vietnam in March 2020. However, in line with the central government’s responses, these local governments effectively controlled the number of infected community cases and continued their socioeconomic development.

Figure 4. Total number of cases of COVID-19 in Hanoi, Da Nang, Ho Chi Minh City, and Vietnam from 22 January 2020 to 9 May 2021

Note. Computed by authors from Open Development Mekong (2021) and World Health Organization (WHO) (2021).

METHODOLOGY

We collected data on cases of infection, death, and recovery from coronavirus (COVID-19) in Vietnam by province from the Open Development Mekong (https://data.vietnam.opendevelopmentmekong.net) and the Dashboard for COVID-19 statistics of the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Vietnam (https://ncov.vncdc.gov.vn/) as of 10 May 2021. The cumulative daily number of confirmed cases and recovered cases of COVID-19 in three cities of Vietnam from 23 January 2020 to 10 May 2021 were encoded into an Excel file.

Regarding country-level and municipal-level responses of Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, and Hanoi, we review relevant documents issued in the online database “Vietnam Laws Repository” https://thuvienphapluat.vn/en/index.aspx) and relevant official websites, such as the MOH website on COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control policies (https://ncov.moh.gov.vn/web/guest/chinh-sach-phong-chong-dich). Four hundred six (406) documents were obtained until 10 May 2021. Because there is no official channel for storing COVID-19 public documents promulgated by district and ward levels in three cities, we could not collect the policy documents under the provincial level (districts and communes) for further analysis. After these documents were organized, we analyzed these local governments' policy evolution according to the three waves of the pandemic.

RESULTS

Vietnam’s Responses to Control COVID-19 at the National Level Based on SDGs

In striving to attain the SDGs, Vietnam also focuses on policies and actions to mitigate poverty, protect the environment, and ensure peaceful life and prosperity for citizens. However, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted Vietnam's socioeconomic life and slowed down the progress in attaining SDGs. In particular, the poor and most vulnerable, including older people, low-wage earners, and informal workers, have been highly affected by the pandemic. Vietnam launched many policy responses to enhance healthcare and social protection for all people, especially the poor and most vulnerable.

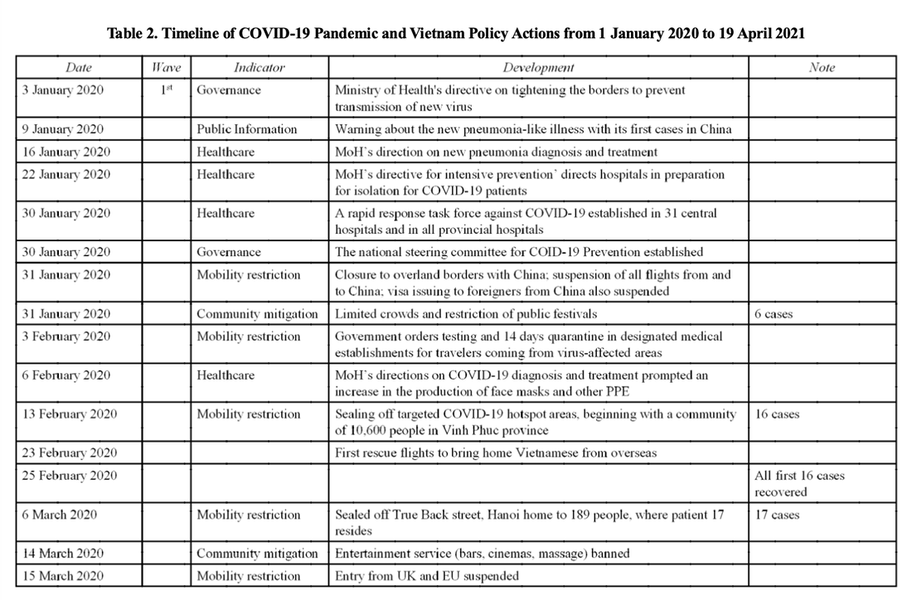

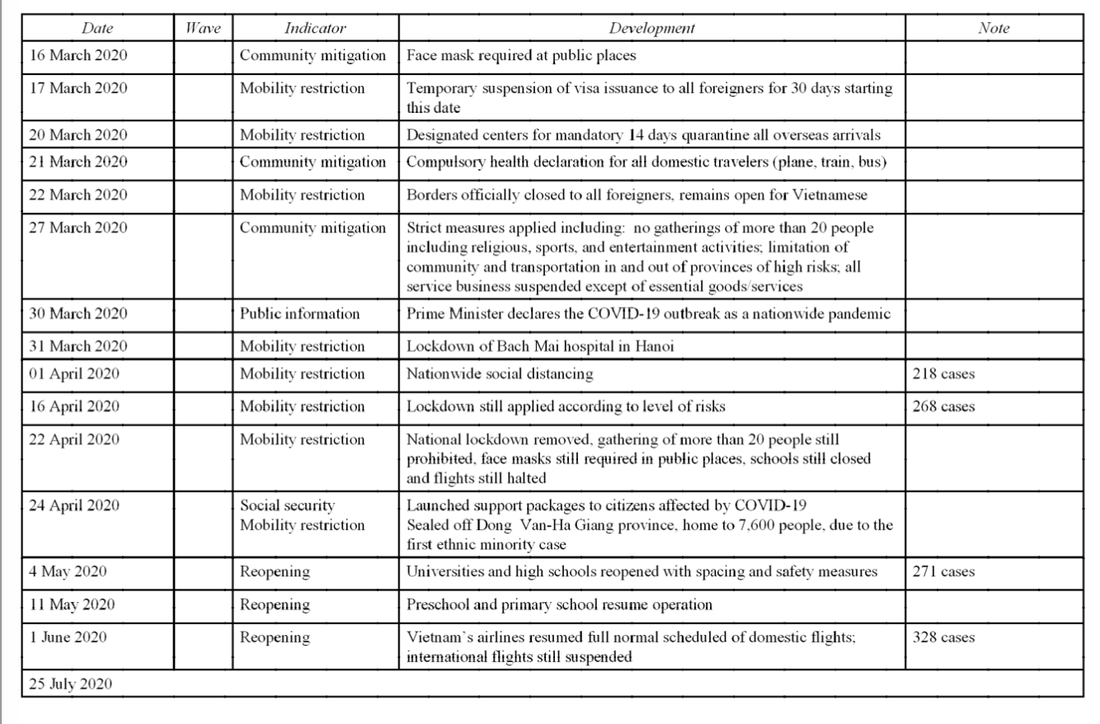

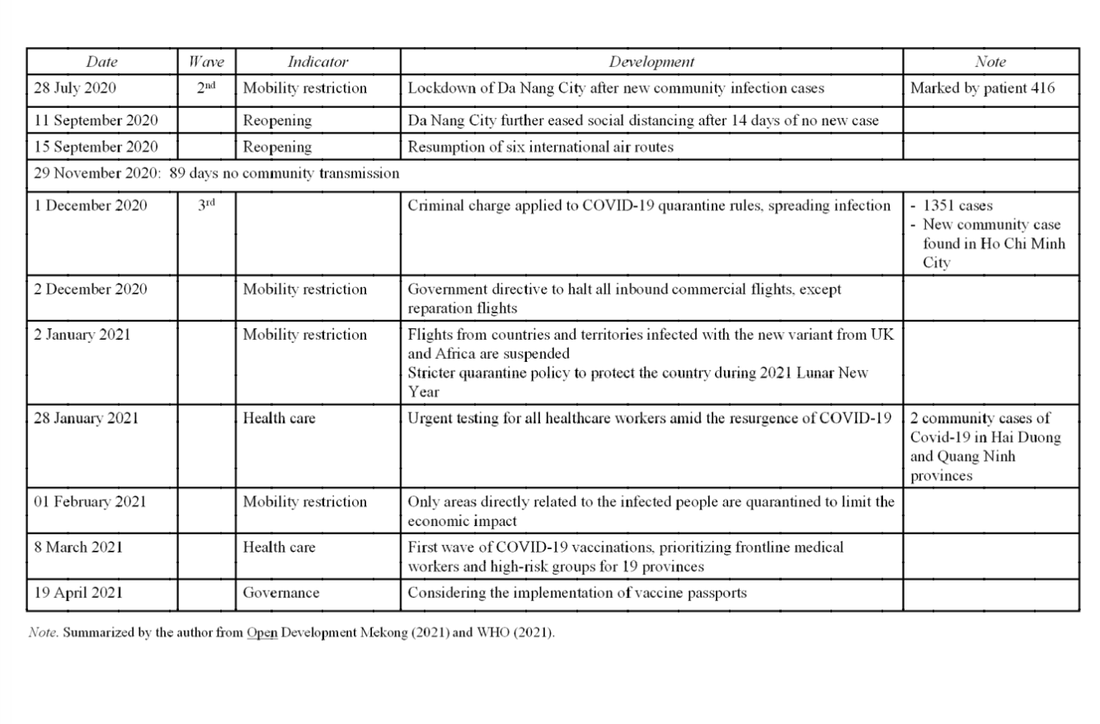

In January 2020, the Government of Vietnam issued the first national response plan and assembled the National Steering Committee to implement this plan. The National Steering Committee is central to the command-and-control governance of the COVID-19 response. From January 2020 to March 2021, the government launched over 200 documents that mainly focused on six dimensions, including governance, public information, healthcare, mobility restriction, community mitigation, and social security (Table 2).

METHODOLOGY

We collected data on cases of infection, death, and recovery from coronavirus (COVID-19) in Vietnam by province from the Open Development Mekong (https://data.vietnam.opendevelopmentmekong.net) and the Dashboard for COVID-19 statistics of the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Vietnam (https://ncov.vncdc.gov.vn/) as of 10 May 2021. The cumulative daily number of confirmed cases and recovered cases of COVID-19 in three cities of Vietnam from 23 January 2020 to 10 May 2021 were encoded into an Excel file.

Regarding country-level and municipal-level responses of Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, and Hanoi, we review relevant documents issued in the online database “Vietnam Laws Repository” https://thuvienphapluat.vn/en/index.aspx) and relevant official websites, such as the MOH website on COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control policies (https://ncov.moh.gov.vn/web/guest/chinh-sach-phong-chong-dich). Four hundred six (406) documents were obtained until 10 May 2021. Because there is no official channel for storing COVID-19 public documents promulgated by district and ward levels in three cities, we could not collect the policy documents under the provincial level (districts and communes) for further analysis. After these documents were organized, we analyzed these local governments' policy evolution according to the three waves of the pandemic.

RESULTS

Vietnam’s Responses to Control COVID-19 at the National Level Based on SDGs

In striving to attain the SDGs, Vietnam also focuses on policies and actions to mitigate poverty, protect the environment, and ensure peaceful life and prosperity for citizens. However, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted Vietnam's socioeconomic life and slowed down the progress in attaining SDGs. In particular, the poor and most vulnerable, including older people, low-wage earners, and informal workers, have been highly affected by the pandemic. Vietnam launched many policy responses to enhance healthcare and social protection for all people, especially the poor and most vulnerable.

In January 2020, the Government of Vietnam issued the first national response plan and assembled the National Steering Committee to implement this plan. The National Steering Committee is central to the command-and-control governance of the COVID-19 response. From January 2020 to March 2021, the government launched over 200 documents that mainly focused on six dimensions, including governance, public information, healthcare, mobility restriction, community mitigation, and social security (Table 2).

Government response to COVID-19 was based on the principle of “protecting people’s health first”, so they accepted economic losses in exchange for the safety of people’s health and lives, minimizing deaths from the pandemic. This is one of the most distinctive features of the COVID-19 policy responses in Vietnam. Measures involving mobility restriction and community mitigation account for 63% (126/200), and healthcare makes up 18% (36/200). In particular, the most widely covered measure was the movement restriction introduced in late January 2020. In addition, various strict measures have been imposed to minimize the spread of the virus in the community and from other affected areas, such as border closure, restrictions on domestic and international movements, school and workplace shutdown, cancellation of public events and gatherings, strict quarantine, social distancing, and effective communication strategies (Tran et al., 2020). Regarding healthcare, the government launched public health education campaign via conventional and social media. Besides, high technology was applied for public health management, such as free mobile applications (e.g. COVID-19, NCOVI, and Bluezone) for all citizens. The user could be alerted if they had close contact with a COVID-19-positive individual, thereby identifying potentially infected patients (Vietnamese Ministry of Health, 2020).

Under the government's strong leadership and effective multisectoral coordination and collaboration, Vietnam successfully implemented COVID-19 prevention, detection, and control activities at the initial stage of the pandemic. Key outbreak response measures have been conducted persistently and strictly, such as early detection, testing and treatment, contact tracing, isolation/quarantine, strategic risk communications, and specific vaccine plans.

Good practices of local governance in Vietnam to control COVID-19: case of three cities

This study the critical role of local governance in coordinating pandemic response by examining how municipal authorities are attempting to bridge the gap between the need for a rapid, vigorous response to the pandemic and local realities in three large cities in Vietnam- the capital Hanoi, Da Nang City and Ho Chi Minh City. Due to each region's different levels of risks and specific character, the provincial governments have more detailed and unique measures to combat COVID-19.

Based on the framework for evaluating COVID-19 responses, these three cities had the valuable experience to offer greater insight into controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. First, three cities had early pandemic prevention and intensive public communication, such as vigorous screening, contact tracing, testing, and quarantining people in affected areas. Second, as the crisis unfolded, the city authorities were ready and able to immediately activate and establish governance systems that would allow inter-agency collaboration in addressing the situation, such as that with the Ministry of Healthor Ministry of Economics. Third, concerning response and recovery, the cities focused on four primary policies: financial and economic aid, social policies, health care policies, and lockdown and restriction measures. Most lessons likely come from tight control, advanced planning, decentralization of the state government, and the flexibility and responsiveness of these local governments. Their policy responses comply strictly with Vietnam's national guidelines and policies concerning the COVID-19 outbreak.

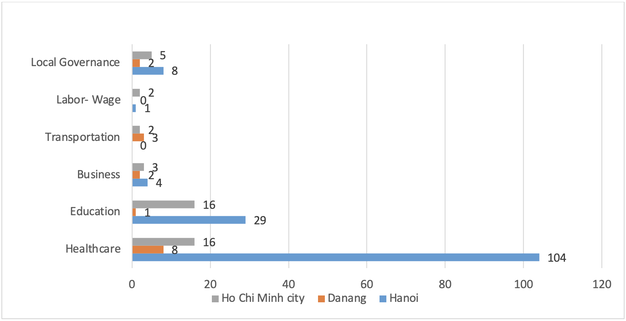

During three waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hanoi, Da Nang City, and Ho Chi Minh City have issued 206 policy documents on specific areas such as healthcare, education, business, transportation, labor, and local governance (Figure 5). Like the national responses, three cities mainly focused on healthcare and education measures in the COVID-19 pandemic, with 174 out of 206 measures. Hanoi launched 133 documents related to healthcare and education measures, accounting for 76.4% of the policy documents. In contrast, the number of records involving these two sectors in Ho Chi Minh only comprised 18.4 percent of the documents. The policy responses related to local governance also became the third significant concern for these three cities, implementing 15 measures. The remaining measures, such as business, transportation, and labor only account for a small proportion of the policy documents. However, each city has other specific ways to control the pandemic effectively.

Figure 5. Responses to Control Covid-19 in Hanoi, Da Nang, and Ho Chi Minh City from January 2020 To April 2021

Under the government's strong leadership and effective multisectoral coordination and collaboration, Vietnam successfully implemented COVID-19 prevention, detection, and control activities at the initial stage of the pandemic. Key outbreak response measures have been conducted persistently and strictly, such as early detection, testing and treatment, contact tracing, isolation/quarantine, strategic risk communications, and specific vaccine plans.

Good practices of local governance in Vietnam to control COVID-19: case of three cities

This study the critical role of local governance in coordinating pandemic response by examining how municipal authorities are attempting to bridge the gap between the need for a rapid, vigorous response to the pandemic and local realities in three large cities in Vietnam- the capital Hanoi, Da Nang City and Ho Chi Minh City. Due to each region's different levels of risks and specific character, the provincial governments have more detailed and unique measures to combat COVID-19.

Based on the framework for evaluating COVID-19 responses, these three cities had the valuable experience to offer greater insight into controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. First, three cities had early pandemic prevention and intensive public communication, such as vigorous screening, contact tracing, testing, and quarantining people in affected areas. Second, as the crisis unfolded, the city authorities were ready and able to immediately activate and establish governance systems that would allow inter-agency collaboration in addressing the situation, such as that with the Ministry of Healthor Ministry of Economics. Third, concerning response and recovery, the cities focused on four primary policies: financial and economic aid, social policies, health care policies, and lockdown and restriction measures. Most lessons likely come from tight control, advanced planning, decentralization of the state government, and the flexibility and responsiveness of these local governments. Their policy responses comply strictly with Vietnam's national guidelines and policies concerning the COVID-19 outbreak.

During three waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hanoi, Da Nang City, and Ho Chi Minh City have issued 206 policy documents on specific areas such as healthcare, education, business, transportation, labor, and local governance (Figure 5). Like the national responses, three cities mainly focused on healthcare and education measures in the COVID-19 pandemic, with 174 out of 206 measures. Hanoi launched 133 documents related to healthcare and education measures, accounting for 76.4% of the policy documents. In contrast, the number of records involving these two sectors in Ho Chi Minh only comprised 18.4 percent of the documents. The policy responses related to local governance also became the third significant concern for these three cities, implementing 15 measures. The remaining measures, such as business, transportation, and labor only account for a small proportion of the policy documents. However, each city has other specific ways to control the pandemic effectively.

Figure 5. Responses to Control Covid-19 in Hanoi, Da Nang, and Ho Chi Minh City from January 2020 To April 2021

Note. Summarized and calculated by author from Vietnam Laws Repository (2021)

First, in the case of Ho Chi Minh City, when the first two cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan were reported on 23 January 2020, the municipal government strictly implemented decisions of the central government, including restrictions on international flights, movement restrictions, school closures, contact tracing, quarantine and social distancing, socioeconomic supports, lockdown, and increasing public health awareness. In particular, based on the “high-risk,” “at-risk,” and “low-risk” ones, Ho Chi Minh City decided to extend the social distancing measures and time off school forpupils, students, and trainees, instead of reopening like other provinces. For instance, in the first wave of the pandemic, the measures in Ho Chi Minh City could be extended until 30 April 2020, instead of 22 April, following Government's Directive No. 16. This directive sets out Vietnam's strongest measures yet for preventing and controlling the COVID-19 virus, in which "families should be distanced from families, villages should be distanced from villages … provinces should be distanced from provinces". Furthermore, regarding labor and social security, Chi Minh City is the first place in Vietnam that launched support packages for citizens affected by COVID-19. On 27 March 2020, the People's Council of Ho Chi Minh City approved a financial package of 2.75 trillion Vietnamese dongs to fight the COVID-19 epidemic (Huong Giang, 2021). The package was used to provide meal subsidies to people under quarantine and daily allowances for medical workers, military staff, and other forces engaged in epidemic control.

Part of the financial package was also reserved for a possible increase in patients and people who would need to be quarantined and teachers and staff members who would lose income during this time. The city was the first one to inventthe "rice ATM" (cay ATM ago) - a 24/7 automatic dispensing machine providing free rice for people out of work during the nationwide lockdown period. Since then, with the help of state social media, similar “rice ATMs’” have been set up in other big cities like Hanoi, Hue, and Da Nang to help poor people survive the pandemic. Furthermore, to prevent foreigners from illegally entering the country, Ho Chi Minh City made an investigation and detection in the whole city in July 2020. In the second and third waves, Ho Chi Minh City also requested people who returned from the high-risk domestic areas to self-quarantine at home, fill up the health declaration form, and notify local health authorities for sample collection and testing. Especially concerning quarantine, authorities in Ho Chi Minh City set up various hotels for quarantine by online booking service instead of the centralized quarantine facilities like before on 2 January 2021. Ho Chi Minh City also launched a set of safety assessment criteria for preventing and controlling COVID-19 for activities of factories, schools, tourism, museums, monuments, library, and sports. Besides involving public services delivery, the People's Committee of Ho Chi Minh City suggested departments, branches, and districts use innovative approaches effectively. The authorities also allow half of the civil servants and public employees to work from home by using technology information applications, such as Facebook and Zalo, during the peak period of the fight against COVID-19. Meanwhile, other employees can work at the office wearing masks and ensuring social distance. This strategy was an excellent opportunity to enhance online public services and promote digital transformation in the public sector.

In the case of Da Nang City, 99 days after the last infection was reported on 16 April 2020, a patient with an unknown source of infection emerged on 25 July 2020, marking the second wave of COVID-19 to return to Vietnam. This wave was much more severe than the first wave in the capital Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Immediately, Da Nangauthorities implemented the previous effective strategies more vigorously and with a broader scope than earlier, including meticulous contact tracing, strict quarantine, and rigorous testing (Sen Nguyen, 2020). The Da Nang Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Da Nang CDC) tested more than 100 people who had been in contact with the patient during the previous days, and locked down five hospitals, including Da Nang C hospital, Da Nang Hospital, Da Nang Orthopedic and Rehabilitation Hospital, and Hoan My Hospital. Simultaneously, the Da Nang city government investigated illegally trafficked foreigners into Da Nang to prevent illegal entry, and applied Directive No. 16/CT-TTg for the closure of workplaces and schools and restrictions on movement within the city. On 5 August 2020, due to anticipating rising numbers of COVID-19 cases, the Da Nang authorities built a temporary field hospital inside the most prominent sports center in the city. In addition, it mobilized hundreds of doctors, nurses, and medical students to combat COVID-19 at its epicenter (Le & Tran, 2021). In light of the complicated situation caused by the peak in number of COVID-19 pandemic cases, the Da Nang government also suspended some non-essential activities, restaurants, eateries, and public vehicles. In addition, it encouraged online commerce and online public services. According to data published by Da Nang Department of Information and Communications, the rate of providing online public services in Da Nang reached 97% by the end of February 2021 (Bao Da Nang, 2021).

In the case of Hanoi, when the first case was confirmed on 6 March 2020, the municipal government quickly the similar strategies to Ho Chi Minh City and Da Nang City, including immediate adoption of masks, widespread testing and quarantine of potentially exposed persons, rapid contact tracing, and shutdown of and workplaces in affected areas. In late March 2020, facing a severe outbreak at Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi leaders rolled out rapid testing, conducting swab tests for over 30,000 patients, medical personnel, and visitors. In addition, Hanoi’s Health Department requested the six mainhospitals to work on scenarios for a possible surge, including plans to add 1,000 beds with high-tech medical devices. The Hanoi Department of Justice timely issued guidance on meting out punishment and the level of charge fees for violations of COVID-19 prevention rules in the capital city amidst the new COVID-19 resurgence (Bao Chinh Phu, 2021). Hanoi also applied tight transportation management, including passenger and goods transport vehicles from other provinces to the city, as the pandemic has become more complicated. Especially regarding some business COVID-19-related restrictions, authorities in Hanoi applied tightened and marginally relaxed measures depending on the level of risks in various districts. In late March 2021, facing a severe outbreak at Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi leaders rolled out rapid testing, conducting swab tests for over 30,000 patients, medical personnel, and visitors. Especially, Hanoi authorities asked citizens to strictly implement the Ministry of Health’s 5K (in Vietnamese) message: khau trang (facemask), khu khuan (disinfection), khoang cach (distance), khong tu tap (no gathering) and khai bao y te (health declaration) (Vietnam News Wire, 2021). Simultaneously, the Municipal Department of Education and Training always asks schools to stand ready for online learning in case of a possible fourth wave of COVID-19 (Huong Giang, 2021).

Discussion and Conclusion

We draw some lessons from the framework for evaluating COVID-19 responses in these three cities. First, concerning the readiness for a pandemic, three cities had early pandemic prevention and extensive public communication. This included stringent screening, contact tracing, testing, and quarantining of people who came from areas affected by the pandemic. Second, in terms of crisis management, the city authorities were ready and able to immediately activate and set up governance systems that would allow inter-agency collaboration in addressing the situation, such as in healthcare or economics, as the crisis unfolded. These systems would allow for inter-agency cooperation in handling the case. Thirdly,the three cities concentrated their efforts on four critical policies regarding response and recovery. These policies included aid in financial and economic assistance, social policies, health care policies, and lockdown and restriction measures. Most of the lessons were likely learned due to the state government's decentralized structure, prior planning, and stringent control, in addition to the adaptability and responsiveness of these local administrations. In general, their policy solutions are not only in strict agreement with the official rules and policies of Vietnam regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, but also have other specific adaptions.

Mainly involving healthcare, their policy responses to COVID-19 have focused on a combination of disease control and treatment measures, such as preparing the hospital facilities with the required technology and essential equipment, building a “temporary field hospital,” and intensifying medical workers from other provinces. Furthermore, based on the specific characteristics of each city, the local authorities also adapted mobility restriction and community mitigation measures; they tightened and marginally relaxed measures to the level of risks of each district; provided hotel quarantine service; extended social distancing; tightly managed transportation from other provinces to the city; and charged fees to violations of COVID-19 prevention rules. Additionally, regarding social security, the local governments have a good budget plan for pandemic prevention, such as financial packages for people under quarantine, daily allowances for people engaging in the work of pandemic control and people losing income and jobs during social distancing. This money was paid entirely by the city’s funds, with additional funds from the national government and other funders. Besides servicedelivery by both the private and public sectors during workplace and school closure, a broad range of choices for online platforms for learning, meeting, shopping, and public services were provided. Then, the local authorities also promoted the application of information technology to ensure accurate and timely collection, synthesis, and analysis of data from which to regularly assess the high-risk level in each area regularly. Finally, city authorities coordinated with other stakeholders from a local governance perspective. They tapped health specialists (to cong tac) to disinfect the facility and coordinate people's movement. Meanwhile, the authorities also encouraged local administrative units and citizens to report home quarantine violations through a mobile app or website, such as Hanoi Smart City, Ho Chi Minh City COVID-19 map, and Da Nang Covid maps (Nguyen & Malesky, 2020).

On the other hand, we can point out the symptoms of COVID-19 responses by the three cities' governments. First, because in these three waves of the pandemic, the ability to spread COVID-19 was not too high, at a small scale, three city governments could easily control it with their above policy responses. However, in the case of the new variant of COVID-19, the problem became more complex. Therefore, they should have active long-term strategies for pandemic preparedness, such as improving the medical system, increasing the speed of getting vaccines, and implementing economic recovery strategies, instead of current passive methods like closing the border and mobility restriction. Additionally, local governments in multilevel governance and the COVID-19 pandemic have not been conducted effectively. The strategy of multilevel governance investigates how national, regional, and local policies interact to tackle the pandemic crisis. However, these three cities have not identified interaction with non-government actors and governance inside and between individual cities or territories.

Local governments’ core functions were radically extended in view of their great importance in containing COVID-19 (Dutta & Fischer, 2021). On the long-term trajectory of COVID-19 response, local authorities play a role in disease control and infection rate, as well as support to protect basic welfare during severe social and economic dislocation. The findings of this study point out challenges as well as successful lessons of these municipal governments in Vietnam (Hanoi, Da Nang City, and Ho Chi Minh City in containing the COVID-19 outbreak through public information, healthcare, adaptive behavior change, mobility restriction and community mitigation measures, social security, services delivery of both the private and public sectors, and local governance. We hope these practices could be helpful for local governance in other countries in the initial stage of the pandemic for similar future outbreaks.

Several significant limitations need to be considered in this study. First, regarding data, there is no official channel for storing COVID-19 public documents promulgated at the district and ward levels of three cities. Therefore, we only analyzed local governments’ responses through the policy documents at the provincial level. Second, at the time of writing this study, Vietnam, as well as three cities, controlled COVID-19 well. However, these successful may betemporary, applicable to the start of the outbreak. Hence, the authorities’ government should focus on strategic planning to combat the uncertainty of the pandemic in the long term, involving multilevel governance, such as vaccine speed-up campaigns, antiviral drug development, supply chain management, and reinventing the economy and society.

First, in the case of Ho Chi Minh City, when the first two cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan were reported on 23 January 2020, the municipal government strictly implemented decisions of the central government, including restrictions on international flights, movement restrictions, school closures, contact tracing, quarantine and social distancing, socioeconomic supports, lockdown, and increasing public health awareness. In particular, based on the “high-risk,” “at-risk,” and “low-risk” ones, Ho Chi Minh City decided to extend the social distancing measures and time off school forpupils, students, and trainees, instead of reopening like other provinces. For instance, in the first wave of the pandemic, the measures in Ho Chi Minh City could be extended until 30 April 2020, instead of 22 April, following Government's Directive No. 16. This directive sets out Vietnam's strongest measures yet for preventing and controlling the COVID-19 virus, in which "families should be distanced from families, villages should be distanced from villages … provinces should be distanced from provinces". Furthermore, regarding labor and social security, Chi Minh City is the first place in Vietnam that launched support packages for citizens affected by COVID-19. On 27 March 2020, the People's Council of Ho Chi Minh City approved a financial package of 2.75 trillion Vietnamese dongs to fight the COVID-19 epidemic (Huong Giang, 2021). The package was used to provide meal subsidies to people under quarantine and daily allowances for medical workers, military staff, and other forces engaged in epidemic control.

Part of the financial package was also reserved for a possible increase in patients and people who would need to be quarantined and teachers and staff members who would lose income during this time. The city was the first one to inventthe "rice ATM" (cay ATM ago) - a 24/7 automatic dispensing machine providing free rice for people out of work during the nationwide lockdown period. Since then, with the help of state social media, similar “rice ATMs’” have been set up in other big cities like Hanoi, Hue, and Da Nang to help poor people survive the pandemic. Furthermore, to prevent foreigners from illegally entering the country, Ho Chi Minh City made an investigation and detection in the whole city in July 2020. In the second and third waves, Ho Chi Minh City also requested people who returned from the high-risk domestic areas to self-quarantine at home, fill up the health declaration form, and notify local health authorities for sample collection and testing. Especially concerning quarantine, authorities in Ho Chi Minh City set up various hotels for quarantine by online booking service instead of the centralized quarantine facilities like before on 2 January 2021. Ho Chi Minh City also launched a set of safety assessment criteria for preventing and controlling COVID-19 for activities of factories, schools, tourism, museums, monuments, library, and sports. Besides involving public services delivery, the People's Committee of Ho Chi Minh City suggested departments, branches, and districts use innovative approaches effectively. The authorities also allow half of the civil servants and public employees to work from home by using technology information applications, such as Facebook and Zalo, during the peak period of the fight against COVID-19. Meanwhile, other employees can work at the office wearing masks and ensuring social distance. This strategy was an excellent opportunity to enhance online public services and promote digital transformation in the public sector.

In the case of Da Nang City, 99 days after the last infection was reported on 16 April 2020, a patient with an unknown source of infection emerged on 25 July 2020, marking the second wave of COVID-19 to return to Vietnam. This wave was much more severe than the first wave in the capital Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Immediately, Da Nangauthorities implemented the previous effective strategies more vigorously and with a broader scope than earlier, including meticulous contact tracing, strict quarantine, and rigorous testing (Sen Nguyen, 2020). The Da Nang Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Da Nang CDC) tested more than 100 people who had been in contact with the patient during the previous days, and locked down five hospitals, including Da Nang C hospital, Da Nang Hospital, Da Nang Orthopedic and Rehabilitation Hospital, and Hoan My Hospital. Simultaneously, the Da Nang city government investigated illegally trafficked foreigners into Da Nang to prevent illegal entry, and applied Directive No. 16/CT-TTg for the closure of workplaces and schools and restrictions on movement within the city. On 5 August 2020, due to anticipating rising numbers of COVID-19 cases, the Da Nang authorities built a temporary field hospital inside the most prominent sports center in the city. In addition, it mobilized hundreds of doctors, nurses, and medical students to combat COVID-19 at its epicenter (Le & Tran, 2021). In light of the complicated situation caused by the peak in number of COVID-19 pandemic cases, the Da Nang government also suspended some non-essential activities, restaurants, eateries, and public vehicles. In addition, it encouraged online commerce and online public services. According to data published by Da Nang Department of Information and Communications, the rate of providing online public services in Da Nang reached 97% by the end of February 2021 (Bao Da Nang, 2021).

In the case of Hanoi, when the first case was confirmed on 6 March 2020, the municipal government quickly the similar strategies to Ho Chi Minh City and Da Nang City, including immediate adoption of masks, widespread testing and quarantine of potentially exposed persons, rapid contact tracing, and shutdown of and workplaces in affected areas. In late March 2020, facing a severe outbreak at Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi leaders rolled out rapid testing, conducting swab tests for over 30,000 patients, medical personnel, and visitors. In addition, Hanoi’s Health Department requested the six mainhospitals to work on scenarios for a possible surge, including plans to add 1,000 beds with high-tech medical devices. The Hanoi Department of Justice timely issued guidance on meting out punishment and the level of charge fees for violations of COVID-19 prevention rules in the capital city amidst the new COVID-19 resurgence (Bao Chinh Phu, 2021). Hanoi also applied tight transportation management, including passenger and goods transport vehicles from other provinces to the city, as the pandemic has become more complicated. Especially regarding some business COVID-19-related restrictions, authorities in Hanoi applied tightened and marginally relaxed measures depending on the level of risks in various districts. In late March 2021, facing a severe outbreak at Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi leaders rolled out rapid testing, conducting swab tests for over 30,000 patients, medical personnel, and visitors. Especially, Hanoi authorities asked citizens to strictly implement the Ministry of Health’s 5K (in Vietnamese) message: khau trang (facemask), khu khuan (disinfection), khoang cach (distance), khong tu tap (no gathering) and khai bao y te (health declaration) (Vietnam News Wire, 2021). Simultaneously, the Municipal Department of Education and Training always asks schools to stand ready for online learning in case of a possible fourth wave of COVID-19 (Huong Giang, 2021).

Discussion and Conclusion

We draw some lessons from the framework for evaluating COVID-19 responses in these three cities. First, concerning the readiness for a pandemic, three cities had early pandemic prevention and extensive public communication. This included stringent screening, contact tracing, testing, and quarantining of people who came from areas affected by the pandemic. Second, in terms of crisis management, the city authorities were ready and able to immediately activate and set up governance systems that would allow inter-agency collaboration in addressing the situation, such as in healthcare or economics, as the crisis unfolded. These systems would allow for inter-agency cooperation in handling the case. Thirdly,the three cities concentrated their efforts on four critical policies regarding response and recovery. These policies included aid in financial and economic assistance, social policies, health care policies, and lockdown and restriction measures. Most of the lessons were likely learned due to the state government's decentralized structure, prior planning, and stringent control, in addition to the adaptability and responsiveness of these local administrations. In general, their policy solutions are not only in strict agreement with the official rules and policies of Vietnam regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, but also have other specific adaptions.